At the height of its power, the Roman Empire imported thousands of animals from Europe, Africa, and Asia for use in annual gladiatorial games. More often than not, these hyenas, lions, tigers, elephants, and other forms of fauna would be released in coliseums during mock hunts, where crowds watched as they served as fodder for archers in chariots. Others met their end in fights against sword-and-shield bearing gladiators. Some of the more fortunate animals entertained audiences by killing and consuming unarmed criminals.

Romans also put on one-on-one death matches between different species, often using animals that had never encountered one another in the wild. For example, they’d tie a bear from northern Europe to an African lion and would use fire to goad the animals into fighting. In other instances, they’d starve two animals, throw them in an arena, and let nature take its course. Usually, these fights were to the death. It’s likely that thousands of these battles occurred over the Roman Empire’s 500-year history.

With such a long, bloody record, it would seem that Rome could answer innumerable “who would win” animal fighting debates. Unfortunately, only a few written accounts of interspecies combat have survived into modern times, and these are severely lacking in specifics. However, these accounts in combination with abundant archaeological evidence—coins, mosaics, and paintings depicting animal-on-animal combat—provide some detail about these horrific battles. Here are ten interspecies fights from Roman history (original descriptions of the fights included at the end of each entry).

10. Tiger v. Lion

Most of our knowledge of interspecies fights comes from the historian Martial, who wrote about the first gladiatorial games in the Roman Coliseum in 80 A.D. Overseen by the Emperor Titus, these inaugural games lasted over 100 days and included gladiator fights and recreations of famous moments from Roman history. At one point, the Coliseum was flooded and actors staged a naval battle. Titus even imported over 5,000 animals for his games. Although most of these fauna died in mock hunts, some met their end in interspecies fights.

A 600-lb Asian tiger and a 500 lb African lion faced off in one of these matchups. Easily procured from nearby North Africa, lions were a common sight in Roman arenas (some Romans even kept lions as pets, with one Emperor using lions to pull his chariot and another releasing lions on unsuspecting dinner guests). Tigers, on the other hand, were much rarer and, as such, they fascinated the Roman populace. One tiger gained fame for being so gentle that it would lick its trainer’s hand.

When attendants chose this particular tiger for an interspecies fight with a lion, the audience predicted an easy victory for the lion. They were wrong. When a trainer loosed the tiger in the Coliseum, something happened. Whether it was the noise of the audience or the site of the lion, the tiger grew enraged. At the first opportunity, the angry tiger chased down the lion, leapt on it, and flipped it on to its back. Using its weight advantage, the tiger then treated the lion as it would any other prey: it used its teeth and claws to open the animal’s undercarriage. Blood and viscera escaped the lion’s abdomen and spilled on to the arena floor.

Although this is the only recorded victory of a tiger over a lion in Roman history, it seems that this matchup happened on other occasions. Tigers almost always emerging the victor.

Lions sometimes came out on top. This mosaic depicts a lion disemboweling either a tiger or a panther.

A tigress that had been accustomed to lick the hand of her unsuspecting keeper, an animal of rare beauty from the Hyracanian mountains, being enraged, lacerated with maddened tooth a fierce lion; a strange occurrence, such as had never been known in any age. She attempted nothing of the sort while she lived in the depth of the forests; but since she has been amongst us, she has acquired greater ferocity. Martial, The Epigrams of Martial 13

9. Bull v. Elephant

The Titus games also featured a fight between an African elephant and a bull. At 10,000 lbs, elephants are the world’s largest land animal, something that made them popular attractions in Rome’s arenas. Romans also liked to watch elephants fight because of the animal’s high level of intelligence and because Carthaginian General Hannibal Barca had used elephants when he invaded Rome in the Second Punic War. Romans wanted to see something defeat the instrument of their greatest enemy. This combination of size, cunning, and historical malignance made the beast an object of derision to Roman citizens.

Unfortunately, the best opponent Rome had for the elephant at the Titus games was a bull (The Romans had a rhino, but didn’t use it. More below). A mismatch today, it was even more so in ancient times. Whereas two thousand years of selective breeding have made modern cattle as heavy as 3,000 lbs and, in the case of Spanish fighting bulls, unnaturally aggressive, bovines in ancient Rome weighed less than 1,000 lbs and were unwilling to fight unless provoked.

In order to put the bull into a fighting mood, then, attendants in the Coliseum held a flame to the animal’s hindquarters and mocked it by rattling nearby straw dummies. The heat and motion enraged the bull, and it charged the dummies, tossing each into the air. When attendants then brought the elephant into the arena, the bull “imagined the elephant might easily be thus tossed,” lowered its head, and charged.

The elephant turned to face the tiny animal coming in his direction, and swung his tusks when the bull came in close. The blow sent the bull reeling, and the animal collapsed. The elephant then finished its downed opponent with a series of stomps and capped off its victory with an impressive display. It sauntered over to the emperor’s podium and knelt. Martial claims that the elephant had not been trained to do so, but was, instead, showing reverence and recognizing the emperor’s divinity.

The bull, which, lately goaded by flames through the whole arena, had caught up and cast aloft the balls, succumbed at length, being struck by a more powerful horn, while he imagined the elephant might easily be thus tossed.

Whereas piously and in suppliant guise the elephant kneels to thee, Caesar,—that elephant which erewhile was so formidable to the bull his antagonist,—this he does without command, and with no keeper to teach him: believe me, he too feels our present deity. Martial, The Epigrams of Martial 13

8. Rhinoceros v. Bull

Yet another bull had to face an oversized opponent as the Titus games: a two-horned East Africa black rhinoceros that likely weighed between 2,500-5,000 lbs. In addition being twice the bull’s weight, the rhino’s duel horns were sharp and fully capable of driving entirely through his opponent’s torso. Although the rhino’s thick hide wouldn’t protect against a direct charge from the bull, any glancing blows would likely have little effect.

The bull did have one advantage: the rhinoceros was probably weak from the 1,200-mile land and sea trip from Africa to Rome. Romans had successfully imported rhinoceroses from both India and Africa for prior games—and some had even been involved in interspecies fights—but the passage was trying and more than one rhino died in transit (after the fall of the Roman Empire, it would be over a thousand years before a rhino arrived in Europe alive). In addition, the rhino was probably weak from not having eaten its normal diet since leaving Africa.

Likely owing to these factors, the rhino appeared lethargic when it entered the Coliseum. The crowd had looked forward to seeing the massive animal fight, but its lack of energy left them disappointed. The bull, on the other hand, was ready to fight.

It didn’t matter. The only description of the rhino-bull brawl says that the rhino tossed the bull into the air as if it were a straw dummy, and, presumably, the bull died shortly thereafter.

Although victorious, the battle with the bull exhausted the rhinoceros, and it walked to the center of the arena, where it lay down to catch its breath, and then fell asleep. It would awaken to find a new opponent.

The rhinoceros, exhibited for thee, Caesar, in the whole space of the arena, fought battles of which he gave no promise. Oh, into what terrible wrath did he with lowered head blaze forth! How powerful was that tusk to whom a bull was a mere ball! Martial, The Epigrams of Martial 15-16

7. Rhinoceros v. Bear

This time, the rhinoceros had to fight a bear. Although it’s unclear what type of bear was brought into the ring—there’s evidence that Romans once used a polar bear in their games—it’s likely the rhino faced a European grizzly. These 600 lb bears make their homes in the northern portions of the Roman Empire and were frequently part of the gladiatorial games.

When the bear was led into the arena, the rhino refused to fight and continued to rest on the arena floor. The animal’s apathy angered the crowd. They grew restless, booed, and complained about the rhino’s inaction until officials dispatched arena attendants to rouse the slumbering beast. Trembling, these men crept into the arena and began poking the rhino with long metal poles until the beast awoke, grew angry, and got to its feet.

Because the attendants had quickly escaped the arena, the poor grizzly would be the target of the rhino’s wrath. When the larger animal saw his bear opponent, he lowered his head and charged. Unable to get out of the way in time, the bear took the full brunt of the rhino’s charge in his belly. As the horns entered the bear’s flesh, the rhino craned his neck and sent his opponent flying. Leaving the bull for dead, the rhino angrily paraded around the arena.

The crowd roared in approval at the rhino’s newfound vigor and called for more challengers.

While the trembling keepers were exciting the rhinoceros, and the wrath of the huge animal had been long arousing itself, the conflicts of the promised engagement were beginning to be despaired of; but at length his fury, well-known of old, returned. For easily as a bull tosses to the skies the balls placed upon his horns, so with his double horn did he burl aloft the heavy bear. Martial, The Epigrams of Martial 15-16

6. Rhinoceros v. Buffalo

5. Rhinoceros v. Panther

(Rhino v. pretty much every other animal the Romans had laying around)

Arena officials obliged. Hoping multiple opponents would make for a better show, attendants released two bulls into the coliseum with the rhino, but the beast promptly “lifted two steers with his mobile neck” and tossed them as he had done his earlier challengers.

The Romans also put a European buffalo into the arena with the rhino. Although his heaviest opponent yet, the rhino seems to have “yielded the fierce buffalo” with ease. An ox met the same fate. When the Romans put a panther into the arena, it was so frightened by the sight of the massive rhino that it fled to the other side of the arena at full speed and ran directly into a wall of spears. In his writings, Martial mocked the crowds who had booed the rhino at the outset of the fights by saying, “go now, impatient crowd, and complain.” He was essentially asking, “Are you not entertained?”

The ultimate fate of the rhinoceros is unknown. A gladiator may have dispatched him, or he may have been kept in the coliseum for use in future games. What is known, is that lamps throughout the empire would depict the rhino’s victory over the bull.

He lifted two steers with his mobile neck, to him yielded the fierce buffalo and the bison. A panther fleeing before him ran headlong upon the spears. Martial, The Epigrams of Martial 15-16

4. Bear vs. Bull

It’s likely that the Titus games also featured at least one confrontation between a bear and a bull, as one Roman author stated that “we often see at a morning performance in the arena a battle between a bull and a bear.” They occurred so often, probably to warm up crowds for later gladiatorial events, that multiple Roman mosaics and paintings of bear-bull fights survive today.

The regularity of these matches likely owed to the ease in which it took to procure bulls and bears and the fact that the animals were fairly evenly matched. A favorite tactic to incite the two animals to combat was for arena workers to tie a rope from one animal’s foot to the other, thereby causing agitation and preventing either animal from running away. When this failed to anger the animals, attendants would try to poke the bear and bulls in order to make them fight. One excited, the animals fought until one “has torn the other to pieces.” Arena attendants would then kill the victor.

Although the only surviving written account of bear-bull combat in Roman arenas lacks detail, most visual depictions of the fights have the bear besting his bovine opponent. This makes sense. Bulls would have a weight advantage over grizzlies, but not the 1,000 lb advantage that today’s heavier bulls would enjoy. In addition, a bull’s strongest asset—its charge—would be negated if it were tied to a bear. The bear, therefore, would be free to bite and claw the bull, while the bull, lacking momentum to puncture, could only scrape.

We often see at a morning performance in the arena a battle between a bull and a bear, fastened together, in which the victor, after he has torn the other to pieces, is himself slain. Seneca Of Anger Book III #43

3. Lion v. Bull

Pitting a lion against a bull was also common in the Roman Empire, but there are no written descriptions of such fights. There are, however, tons of coins, murals, and mosaics bearing illustrations of lion-bull combat. If anything is to be learned from these depictions, it’s that lions kicked the hell out of bulls. Pictures show lions ripping into bulls’ necks, jumping on a down bull, and clawing at a bull’s face. Only a handful depict a bull piercing a lion with its horns.

This type of combat seems to have outlasted the Roman Empire, as at least one piece of Byzantine art depicts a lion dispatching a bull in an arena.

Byzantine art with lion dispatching a bull. What’s going on with the rest of this thing? There’s the guy with the beehive head, a horse kicking a bear, a man shooting something out of his side into a bear’s chest, another bear attacking a dude in a cage, and, of course, creepy, weird guy in the lower left corner taking it all in.

2. Lion v. Bear

Lions and bears also fought, but like with the lion-bull fights, only visual depictions remain as evidence that they happened. Unlike the lion-bull fights, there are not enough illustrations to draw conclusions about who got the better in such contests.

1. Rhino v. Elephant

The ultimate in interspecies combat, a fight between the two largest land animals, happened at least two times, and possibly more, in the Roman Coliseum. The first of these battles took place at Emperor Augustus’s gladiatorial games in 8 A.D. Unfortunately, the only person who wrote about the fight noted merely that “an elephant overcame a rhinoceros.” Although this version of the fight is lacking in detail, a possibly apocryphal telling of the bout has the elephant picking up a spear used in an earlier event and chunking it through the rhinoceros’s eye. The elephant then stomped its blinded opponent to death. Although the source of this information is uncited, such a scenario is plausible. When gladiators cut the legs of an elephant in a different matchup, the animal dropped to its knees, used its trunk to grab its opponents’ shields, and slung the discs back at their owners.

Although a rhino lost the first recorded battle with an elephant, it appears one of its brethren evened the score. In 55 A.D., at Pompey’s games, Pliny the Elder noted cryptically that a single horned rhino had been trained in Rome to “fight matches with an elephant.” Pliny stated that the rhino filed his horn against stones in preparation for battle and once fighting began, the animal would “aimeth principally at the belly, which he knoweth to be the tenderest part.” This language seems to indicate that the rhino had been in multiple battles with elephants, which, in turn, would mean that he’d defeated multiple elephants. After all, if the rhino had died after the first fight with an elephant, Pliny would be unable to have written about the animal’s activities as if they were habits.

Beyond these few words, there are no records of these fights. Although the elephant and rhino at the Titus games dispatched multiple smaller opponents, there’s no record of them fighting each other.

This lasted till the scarcity of grain subsided, when gladiatorial games in honor of Drusus were given by Germanicus Caesar and Tiberius Claudius Nero, his sons. [In the course of them an elephant vanquished a rhinoceros and a knight distinguished for his wealth fought as a gladiator. Dio’s Roman History LV 479

In the same Plays of Pompey, and many Times beside was shewed a Rhinoceros, with a single Horn on his Snout. This is a second begotten Enemy to the Elephant. He fileth this Horn against hard Stones, and so prepareth himself to fight; and in his Conflict he aimeth principally at the Belly, which he knoweth to be the tenderest Part. He is full as long as his enemy; his Legs much shorter; his Colour a palish Yellow. Pliny Natural History Book VIII 36

Conclusion

Other forms of interspecies combat took place in Roman arenas, but we know even less about them than the fights above. A painting shows an ostrich taking on a lion, a gemstone depicts a lion dispatching a crocodile, and a written account implies that a hippopotamus fought a crocodile. Unless more Roman texts turn up, the above descriptions will have to suffice for those wanting to know more about animal-on-animal combat.

Brad Folsom

Notes:

Interpretations of primary sources are my own as well as those of the following two sources.

Epplett, William Christopher, “Animal Spectacula of the Roman Empire,” Ph.D. Dissertation The University of British Columbia, 2001.

Jennison, George. Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Whenever forewarned of the enemy’s approach, Mexican fathers kissed their wives and children goodbye and then hid them in compartments under floorboards, hoping to save their families from a fate worse than death. Children would then watch from cracks in the floor as shadowy figures entered their homes and turned their fathers into pulp.

Every year in the mid-nineteenth century, thousands of mounted Comanche, Apache, and Kiowa Indians left their homeland on the Southern Plains of Texas to pillage remote frontier settlements in northern Mexico. They came to plunder, stealing livestock and sundry goods to sell to American settlers in Texas. The Indians also came for vengeance. They had lost countless family members in years of war with Mexico and sought to avenge their fallen comrades by torturing and killing as many Mexicans as they could. It was gruesome. Indians mutilated and scalped men. Gang raped and killed women. Children were left to die or were kidnapped and forcefully incorporated into Indian tribes.

The brutal Indian attacks sent survivors fleeing to the protection of well-populated cities, leaving small villages throughout northern Mexican ruined, depopulated husks. Adobe skeletons dotted the countryside, prompting one observer to remark that northern Mexico had become a land of a thousand lifeless deserts.

This “War of a Thousand Deserts” between Southern Plains Indians and the people of northern Mexico is the subject of two of the most haunting literary works of the past thirty years. Brian Delay’s nonfiction War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War is a scholarly history of Indian raids before the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-1848. Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness of the West is historical fiction that uses this turbulent time in northern Mexico as its background. Both are tremendous reads that are far more frightening than works that rely on the supernatural for scares. They should be read by anyone who wants to understand true terror.

McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness of the West tells the story of “The Kid,” an American youth who travels to Mexico and the U.S. Southwest seeking fortune and an outlet for his violent nature. The Kid begins his journey in Texas, but soon makes his way to Mexico as a part of a filibustering expedition (filibusters were private American armies that invaded Mexico for land or plunder). After Comanches annihilate The Kid’s filibustering outfit, the young man joins a scalp hunter gang made up of fellow Americans. In the novel as well as in reality, Mexican officials, lacking soldiers and firearms, often hired American mercenaries to retaliate against Indians. The men were paid based on the number of Indian scalps they collected.

The remainder of Blood Meridian follows The Kid and his menagerie of psychopaths across a Mexican countryside devastated by Indians attacks past the snowy mountains of New Mexico and into the sweltering Arizona desert.

Although its characters are fictional, Blood Meridian’s bleak portrayal of Mexico and the American Southwest in the mid-nineteenth century is historically accurate and provides a dark counterpoint to traditional westerns. Most movies and books on the post-Civil War American West feature Indians or outlaws threatening law-abiding whites until heroes arrive to re-establish the status quo. Although feature films and novels often overplay the violence of the American West in the late 1800s, they correctly portray a conclusion where local or national governments eventually restored order.

There was little order in Mexico and the Southwest from 1836-1870. There were no heroes to save the day. That’s what makes Blood Meridian so haunting and so accurate. The reader constantly searches for a character with a sense of humanity. Someone to give them hope. But just as it was in Mexico, there are none to be found.

Brian Delay’s nonfiction War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War is a perfect companion to Blood Meridian, as it uses facts and figures to show the extent of Indian depredations in Mexico’s North. Delay’s book contradicts modern portrayals of Indians as noble warriors who fought with ferocity to protect their families and their land. Instead, the Indians who invaded Mexico were more like Mongols. They formed massive armies and plundered the weak for personal gain. They derived pleasure from their enemies’ suffering. They were effective and far-reaching, with one Indian army raiding within 100 miles of Mexico City.

In spite of the ferocity of the attacks, the people of northern Mexico could expect little help from their government, as politicians maintained the army in the capital to protect against frequently occurring coups. The fate of peasants on the frontier was of little concern to those worrying about political opponents with guns. Delay highlights the Mexican government’s disregard for its northern citizens, by quoting one president, who, when asked why he wasn’t doing anything about Indian depredations, replied, “Indians don’t unmake presidents.”

As War of a Thousand Deserts makes clear, even if there were available soldiers, the Mexican government could do little to stop the Indian attacks. In 1836, the primarily Anglo citizens of Texas had declared independence, broken away from Mexico, and formed their own republic. This left the Southern Plains in a foreign country. In order to attack the Indians in their homes—which, in the past, had proven to be the only effective means of deterring future raids—Mexican soldiers would be invading a neighboring nation and possibly inciting a war. Because the Mexican government was unwilling and unable to commit its army to such an endeavor, Indians raided Mexico from Texas with impunity.

Texans and later Americans even encouraged raids. They bought horses and livestock from Indians knowing that they’d been stolen from within Mexico and their superior technology ensured that Indians would rather deal with poorly-armed Mexicans than Texans and American soldiers with six shooters.

Delay’s book ends with U.S. annexation of Texas and the U.S.-Mexico War from 1846-1848. When American soldiers invaded Mexico at the start of the war, they encountered Indians returning north with spoils from small Mexican villages. Because the Americans had claimed to have the moral high ground in the war and had invaded, in part, under the pretext of providing protection to Mexican citizens, the Indian raiders left them in a quandary. Should they stop the raids, or, since the Indians were attacking the enemy, should they allow them to proceed unmolested?

Mexico’s eventual defeat and the signing over of New Mexico, Arizona, and California to the United States created another conundrum for U.S. officials. One of the conditions of Mexico’s surrender was that the U.S. would stop Indian raiders from entering Mexican territory. After it became clear that they’d be unable to meet this demand, U.S. officials paid off a sitting Mexican president to forget this part of the contract. The raids continued until the 1870s, ending only when Americans eventually moved on to the Southern Plains and forced Indian raiders on to reservations.

The War of a Thousand Deserts was one of the most horrific times in North American history. As Cormac McCarthy’s fictional Blood Meridian and Brian Delay’s nonfiction, War of a Thousand Deserts, make clear, northern Mexico and parts of the Southwest in the mid-1800s became desolate wastelands owing to Indian depredations. Unlike the inhabitants of the later American West, who could expect help in the case of an Indian attack, the people of Mexico could look forward only to death and further suffering. Read Blood Meridian and War of a Thousand Deserts to capture this sense of horror, hopelessness and desperation.

Brad Folsom

4. THE AURORA ALIEN

The Supernatural Story

On April 17, 1897, The Dallas Morning News reported that “an airship” had crashed into a water tower in the nearby town of Aurora. According to local residents, they’d seen the vessel in the skies on earlier occasions, but it had remained silent and distant. On April 16, however, it emitted a screeching sound shortly before falling out of the sky. When residents investigated the crash, they found the vessel destroyed. They described the wreckage as being made of “a mixture of aluminum and steel,” but were unable to locate any form of locomotion.

The most shocking aspect of the Aurora crash was that residents recovered a body at the crash site. The Dallas Morning News reported that the “remains are badly disfigured, [but] enough of the original has been picked up to show that he was not an inhabitant of this world.” An army officer on the scene “gave the opinion that he was a native of the planet Mars.” Perhaps confirming the being’s extraterrestrial origins, residents found papers in the wreckage covered in indecipherable hieroglyphics. The day after the crash, the people of Aurora buried their alien in an unmarked grave in the local cemetery.

The Boring Reality

Aurora resident S.E. Haydon wrote the story for the Dallas Morning News and probably made it up. At the time of the article’s publishing, Haydon’s town was dying. Aurora residents made their money exclusively from cotton at a time when much of the rest of the South was diversifying their economies. A known practical joker, Haydon likely concocted the alien story to draw attention to his town in the hopes of bringing in investors and tourists.

3. THE WOMAN IN BLUE

The Supernatural Story

In 1629, Jumano Indians approached Spanish missionaries in New Mexico claiming that a white woman dressed in blue had recently appeared in their West Texas village. The Indians claimed that this “woman in blue” had taught them the basics of Christianity and had told them to seek out missionaries for further instruction. After hearing the Jumanos’ story, the missionaries traveled to the Indian village and found that, on advice from the woman in blue, 2,000 converts had already prepared for their arrival. The priests baptized the Indians and took testimonial from witnesses claiming to have seen the mysterious woman appear and disappear without a trace.

The story gets more interesting. Throughout the 1620s, a nun in Spain named María de Jesús de de Agreda began to fall into deep trances. Upon awakening, she would claim to have made spiritual visits to Indian tribes in North America to teach Christianity. According to the nun—who was always adorned in a blue habit—one of these groups lived near New Mexico. After hearing María de Jesús’s story, her superiors sent a letter to the missionaries of New Mexico asking if they could verify its veracity.

New Mexico missionary Fray Alonso de Benavides read the letter from Spain and was astonished, as it seemed to confirm the Jumanos’ account of the woman in blue. Benavides went so far as to travel to Spain to speak to the nun personally. During their conversation, María de Jesus confirmed that she was the woman and blue and had visited the Jumanos during her trances. She even described the landscape of New Mexico and West Texas, imitated Jumano tribal gestures, and gave an accurate depiction of a one-eyed Indian. Benavides left Spain convinced that María de Jesus’s story was true.

The Boring Reality

In all likelihood, the Jumanos made up their end of the story. Throughout the early 1600s, the tribe was under constant attack from the warlike Apaches. The Jumanos likely hoped that if Spanish missionaries came to their village, they’d bring along Spanish soldiers to fend off the Apaches. The Jumanos were familiar with Catholic belief in the supernatural, so they concocted a story that would be perceived as divine to offer extra motivation for missionaries. (This wouldn’t be the only time the Jumanos would try this approach. They later claimed that a giant cross appeared above their village). But why choose a woman in blue? Whenever Spanish missionaries traveled, they carried a banner of the Virgin Mary, which just happens to look like:

Sister María de Jesús probably picked up information about New Mexico and West Texas from the numerous North America exploration narratives floating around Spain. As for the tribal gestures, multiple cultures share common hand signals and the Spanish had no catalogue of Indian sign language. For all Benavides knew, María de Jesús could have been signing the Jumano equivalent of “I can’t believe he’s buying this crap.” And the sister’s description of the one-eyed Indian chief didn’t have to be accurate. Owing to racism, the Spanish often confused two different Indians they knew personally. Someone describing an Indian thousands of miles away could make a few mistakes without raising eyebrows. It’s unclear why María de Jesús made her story up, if she did, but it wouldn’t be a difficult hoax to pull off.

2. THE TRAITOR’S GHOST

The Supernatural Story

In August 1815, in the midst of Mexico’s War for Independence from Spain, Ignacio Arocha began telling friends and neighbors an intriguing story. He claimed that the ghost of Ignacio Elizondo had recently visited his wife and servant at his ranch in Texas. Elizondo’s apparition was appearing to ask for repentance, as he’d been damned to hell for “following the unjust cause.” Before disappearing, Elizondo left a handprint on the Arochas’ door as proof of his visit. Following the appearance, curious sightseers flocked to the Arochas’ ranch to see the handprint for themselves.

Known as “the traitor” in Mexican history, Elizondo was infamous for betraying revolutionary leader Father Miguel Hidalgo in 1811 and turning him over to Spanish authorities. After Hidalgo’s capture and execution, Mexico’s revolution against Spain fell apart. Elizondo led a brutal reprisal against those in Spanish Texas who’d supported revolution. Hundreds were executed. One soldier became so sick with the killings that he stabbed Elizondo in the stomach. The Traitor died on the banks of the San Marcos River, where he remained, apparently, until choosing to haunt the Arochas.

The Boring Reality

After hearing of Arocha’s claim, the Spanish government called dozens of witnesses to determine if the story had any truth. The witness testimonials showed that details of Arocha’s story changed over time, with the tale growing more dramatic with each rendition. Not only that, but one witness was convinced that he’d seen Arocha paint the ghost handprint. Finally, Spanish officials discovered that Arocha was a revolutionary sympathizer. The evidence convinced authorities that Arocha had invented the ghost story to recruit followers to the side of independence.

1. THE BIGFOOT

The Supernatural Story

In 1536, Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca returned from an eight-year sojourn in North America. He’d arrived in North America as part of a 600-man Spanish army, but after a shipwreck, conflict with Indians, starvation, and thousands of miles traveling across hostile jungles and deserts, only Cabeza de Vaca and three companions remained. The journey was epic, the four men becoming the first non-Indians to step foot in what would one day become Texas. When they returned to Mexico City and the company of other Europeans, Cabeza de Vaca relayed details about the people, animals, and environment he’d encountered. His stories were incredible, but one tale stuck out more than any other: Cabeza de Vaca had found evidence of a magical, hairy creature named Mala Cosa. (We’ve written about this before. Click here to read the story in greater detail.)

While traveling in South Texas, the Spaniards came upon a village of Indians that had huge scratches on their abdomens. When Cabeza de Vaca asked what happened, the Indians remarked that a short, hairy creature had attacked their village, stolen their food, and cut anyone who opposed him with a sharp flint knife. Perhaps more amazingly, the creature—whom Cabeza de Vaca called Mala Cosa—had superhuman strength and could lift an Indian hut singlehandedly. Cabeza de Vaca was not one to believe in the supernatural, but the detailed stories and scars convinced him that a weird creature had really attacked the Indian village fifteen years before.

The Boring Reality

The Indians probably made up Mala Cosa or had had an earlier encounter with a lost Spaniard who wasn’t as friendly as Cabeza de Vaca. The year that Mala Cosa supposedly appeared in the Indian village, two Spanish expeditions explored areas adjacent to what is today Texas. It’s possible that a member of these expeditions became lost and wandered into the Indian village. If so, he would have been hungry and would have used his sharp steel to take the Indian’s food—just as Mala Cosa had done with his flint knife. Because the European would have had a hairy face and been wearing unusual clothes, the Indians may not have recognized him as human. Hence the origin of Mala Cosa.

Does anyone know of other paranormal stories from Texas history? If so, let us know in the comments.

Bradley Folsom

Remember, remember, the 5th of November; The Gunpowder Treason and plot; I see of no reason why Gunpowder Treason Should ever be forgot. English rhyme

People should not be afraid of their governments. Governments should be afraid of their people. V in Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta

The single horseman, clad in a military dress, and bearing a drawn sword, rode onward as the leader, and, by his fierce and variegated countenance, appeared like war personified. Nathaniel Hawthorne “My Kinsman, Major Molineux”

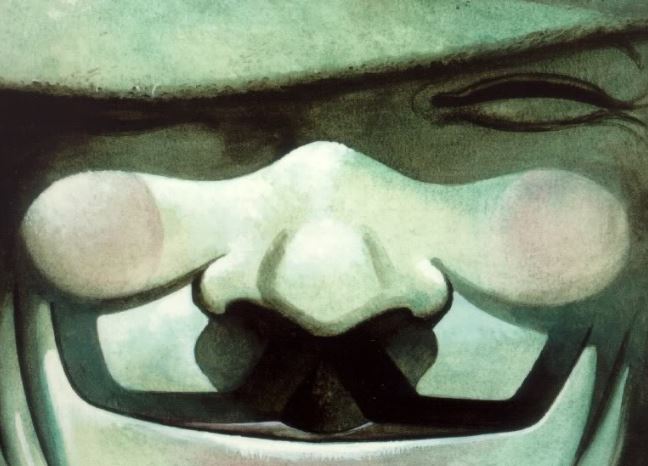

In Alan Moore’s 1988 fictional comic series V for Vendetta—and the 2005 film of the same name—a masked hero incites the British people to revolt against their tyrannical government. Motivated by vengeance and displeasure with British leader Adam Susan, the protagonist, referred to simply as “V,” bombs government targets and takes over media outlets to spread his anti-establishment message. He does these things while adorned in a Guy Fawkes’s mask. Fawkes had been a real life conspirator who was executed after a failed attempt to bomb the British House of Lords on November 5, 1605. Like Fawkes, V dies before carrying out his plan, but his message lived on, encouraging the British public to rise in opposition to the ruling regime.[i]

The United States had a real life version of V. Shortly before the American Revolution, a masked man prowled Boston, attacking British officials and encouraging the people of America to overthrow their colonial masters. Like V, the cloaked dissident identified with a deceased revolutionary from English history. He called himself Joyce Junior, an homage to George Joyce, a man who’d beheaded an English king.

Joyce Junior’s story began in 1763 with Britain’s victory over France in the costly Seven Years War. To repay war debts, British Parliament increased duties on its American colonies and began interfering in government affairs that had previously been the dominion of the colonial assemblies. These changes incensed colonists, especially those schooled in the Enlightenment literature that denied the divine right of kings and called for individual liberty and representative government.

By 1765, some in Britain’s New England colonies began to show their displeasure with the mother country through protest, boycotts, and membership in subversive organizations like the Sons of Liberty. Others expressed their disapproval with violence. When Britain attempted to implement a tax on colonial paper, mobs took to the streets of Boston, beheaded likenesses of British officials, and burned government buildings. Following an increase in duties on tea, Bostonians not only boycotted British tea, but assaulted duty collectors and subjected them to demeaning punishments.

War Personified

Joyce Junior led some of these attacks. Although descriptions of the revolutionary are rare and devoid of detail, witnesses remember a masked man riding into Boston atop either a donkey or a white steed. He draped a long red cloak over a military uniform and jackboots, and carried a cutlass at his side. Completing his image, he wore a white wig and covered his face with a “horrendous” mask. Although sources are unclear on what the mask looked like, it may have been the visage of a demon, a common facade in New England parades.[ii]

The mask may have also been an executioner’s hood. As Guy Fawkes had been for V, a conspirator from British history served as inspiration for Joyce Junior. In 1647, George Joyce and an army of 500 revolutionaries arrested English King Charles I and demanded he institute universal suffrage, religious tolerance, and term limits for parliament. When Charles I refused, George Joyce donned an executioner’s mask and beheaded him. Joyce Junior, then, was the self-designated heir to a man who’d brought down a king.[iii]

Adorned in his mask and elaborate costume, Joyce Junior would ride into Boston and let loose a distinctive whistle to call fellow revolutionaries to his side. The mob would then drag British officials out of their homes, strip them naked, and cover them in a coat of blistering tar and dirty feathers, a painful, sometimes deadly, punishment. Joyce Junior and his mob would then parade the loyalist through the streets of Boston, naked except for their new plumage.

Perhaps the best description of Joyce Junior comes from Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter. Although he was born after the American Revolution, Hawthorne grew up hearing stories about Joyce Junior, which inspired him to write his haunting poem “My Kinsman, Major Molineux.” Set in pre-revolutionary Boston, the poem’s protagonist is a young boy named Robin who came to Boston to work with his British officer uncle, Major Molineux. Unable to locate his relative, the boy wanders Boston’s streets until nightfall when….

A mighty stream of people now emptied into the street, and came rolling slowly towards the church. A single horseman wheeled the corner in the midst of them, and close behind him came a band of fearful wind-instruments, sending forth a fresher discord, now that no intervening buildings kept it from the ear. Then a redder light disturbed the moonbeams, and a dense multitude of torches shone along the street, concealing, by their glare, whatever object they illuminated. The single horseman, clad in a military dress, and bearing a drawn sword, rode onward as the leader, and, by his fierce and variegated countenance, appeared like war personified: the red of one cheek was an emblem of fire and sword; the blackness of the other betokened the mourning that attends them. In his train were wild figures in the Indian dress, and many fantastic shapes without a model, giving the whole march a visionary air, as if a dream had broken forth from some feverish brain, and were sweeping visibly through the midnight streets. A mass of people, inactive, except as applauding spectators, hemmed the procession in, and several women ran along the side-walk, piercing the confusion of heavier sounds, with their shrill voices of mirth or terror.

The leader turned himself in the saddle, and fixed his glance full upon the country youth, as the steed went slowly by. When Robin had freed his eyes from those fiery ones, the musicians were passing before him, and the torches were close at hand; but the unsteady brightness of the latter formed a veil which he could not penetrate. The rattling of wheels over the stones sometimes found its way to his ear, and confused traces of a human form appeared at intervals, and then melted into the vivid light. A moment more, and the leader thundered a command to halt: the trumpets vomited a horrid breath, and held their peace; the shouts and laughter of the people died away, and there remained only a universal hum, allied to silence. Right before Robin’s eyes was an uncovered cart. There the torches blazed the brightest, there the moon shone out like day, and there, in tar-and-feathery dignity, sat his kinsman Major Molineux!

Robin and his uncle had met Joyce Junior. Although fictional, Hawthorne’s account of masked man leading revolutionaries through Boston matches contemporary descriptions of Joyce Junior.

The Red-Cloaked Man

In addition to his attacks upon British officials, Joyce Junior may have been present at, and may have instigated, the Boston Massacre. On March 5, 1770, with tensions high over a recently passed duty, hundreds of angry colonists began throwing snowballs, ice, and rocks at a group of British soldiers guarding Boston’s customs house. Frightened for their lives, the soldiers opened fire on the crowd, killing five. The incident, which the press portrayed as a massacre, convinced many colonists that a break from the mother country was necessary, effectively sending Boston on the road to revolution. The massacre forced the British to rescind duties and pull troops from Boston to avert war.

Three eyewitnesses to the massacre saw “a tall man in a red cloak and white wig” inciting colonists with anti-British rhetoric shortly before the shooting. Leading a crowd in shouts of “huzzah,” the red-cloaked man told his audience to retrieve their weapons and confront the soldiers at the custom’s house. When they did so, and the British soldiers raised their weapons in fear, a shadowy figure that may have been Joyce Junior taunted them to “Fire, Goddamn you! Fire!”[iv]

Did Joyce Junior spark the massacre that led the American colonies to the brink of revolution? Was he this “man in a red cloak”? Some Bostonians thought so. Although Boston newspapers wouldn’t make the connection, they grew infatuated with the red-cloaked man. They speculated that he was “powerful” and had “formed a plan” to create the chaos on March 5th. The Boston Gazette even asked its readers to provide information on the man’s identity, but no one came forward.[v]

Chairman of the Committee for Tarring and Feathering

Although he’d been active in Boston for some time, the name Joyce Junior didn’t appear in print until early January 1774. From then until April 17 of the same year, a series of handbills appeared throughout Boston denouncing the recently passed Tea Act, which lowered prices on British tea to help the British East India company sell its tea surplus. Fearing this cheaper tea would undercut patriot-friendly smugglers, many Bostonians boycotted those selling British tea. The subversive Sons of Liberty went further. In December 1773, they dressed like Indians and threw three shiploads of British tea into Boston Harbor.

Although there’s no evidence that Joyce Junior was in attendance at what would come to be known as the Boston Tea Party, the masked patriot did work to stop people from purchasing British tea. Upon hearing that British officials would be coming to Boston to collect duties on tea, Joyce Junior posted flyers asking citizens to give these duty collectors “a reception as such these vile ingrates deserve.” Signing off as, the “Chairman of the Committee for Tarring and Feathering,” Joyce Junior warned that anyone who tore down his flyer should expect retribution.

It appears that the flyer had its desired effect. Shortly after it was posted, revolutionaries in nearby Marblehead tarred and feathered a group of British officials and dragged them through town until 2 A.M. The next morning a crowd dragged these same officials out of bed and applied a second coat of tar. A few days later a mob chased a duty collector out of Boston. It’s unclear if Joyce Junior led these attacks or if his words inspired others to action, but the results were the same: British officials were leaving New England or facing public humiliation. Although some newspapers lamented that the masked man and his followers were too violent, others reprinted his proclamations for everyone to read. The Boston Gazette even ran advertisements for “damaged feathers” and “an old horse cart” alongside Joyce Junior’s writings.[vi]

By March 1774, everyone in New England had read about Junior Junior’s campaign against British tea. When a vendor continued to sell British tea and mocked his neighbors for supporting the embargo, Joyce Junior placed a note of warning on the man’s door. Upon reading the threatening note, the man cried and stopped selling British tea. When someone bought boycotted goods at two in the morning one night, Joyce Junior placed a flyer on their door warning them to return the articles or face “the resentment of an insulted and injured people.”[vii]

In April 1774, Joyce Junior’s flyers took on a more alarming tone. That month, the people of Boston received word that the British King, George III, had ordered the town’s port closed as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, an edict that promised to crush the economy of the trade-dependent city. To intimidate potential revolutionaries, King George also ordered 4,000 British soldiers to occupy Boston.

Although the presence of British soldiers in Boston slowed mob violence, it didn’t stop Joyce Junior from placing flyers throughout town. Calling Britain the natural enemy to America’s prosperity, the masked patriot implored the people of Boston to “Rouse, rouse my countrymen. Expatriate the viper that is gnawing at our vitals.” He finished, “let us honor ourselves, and we cannot fail of honoring our country.”

It’s unclear if Joyce Junior’s words influenced anyone, but the people of Boston and outlying cities did “rouse” in April 1775 when revolutionary militiamen fired on British soldiers at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The outbreak in fighting convinced others in Britain’s thirteen American colonies that the time for independence was at hand. So in September 1775, colonial representatives met in Philadelphia, created an army, and sent George Washington to eject the British from Boston. He did so in March 1776. Seven years later, the British military left all of the colonies after the United States won its independence from the mother country.

Much like V in V for Vendetta, Joyce Junior incited a war, but left the fighting for others. Unlike V, who dies at the end of his comic series, Joyce Junior simply retired from public view for a short while. In March 1777, however, handbills appeared throughout Boston announcing that Joyce Junior had returned “after almost two years absence” to deal with remaining British loyalists.

As described by future First Lady Abigail Adams, Joyce Junior carried through with his promise in the early morning hours of March 19, 1777. Followed by a mob of 500, the masked revolutionary broke into the home of five loyalists, dragged the men into the streets in their pajamas, and loaded them on to a horse cart. Holding his sword in the air and riding at the head of his makeshift army, Joyce Junior escorted the captives thirty miles out of town, dumped them, and told them not to return to Boston. It’s unclear why Joyce Junior chose these particular men—as more than five loyalists remained in Boston—but rumor had it that they’d intentionally bid high to raise prices at an auction. One man, Harry Perkins had a notoriously rotten son who borrowed money throughout Boston and then ran off to New York before repaying his debts.[viii]

“Is Joyce Junior no more?”

Although this would be Joyce Junior’s last high-profile public appearance, newspapers continued to publish news about the masked man. If reports are to be believed, it seems that Joyce Junior refocused his hatred from the British on to business owners who ripped off customers. For example, a letter from Hartford, Connecticut reported that Joyce Junior had just passed through town, so “Monopolizers and forestallers beware.” A handbill signed by Joyce Junior railed against property owners charging tenants high rent. Another lamented that a single person had created a monopoly of the Boston press by purchasing four of six local newspapers. It’s unclear if these messages were from the real Joyce Junior or if a copycat used the masked man’s signature to lend aplomb to their personal political stances.

Whatever the case, after 1777, Joyce Junior would no longer roam the streets of Boston with his personal army. When the United States achieved its independence from Britain, the same politicians who’d been brought to power by mob violence passed laws to prevent such violence from being used against them. They also implemented new taxes and supported wealthy elites with ties to the national government. One Bostonian, angry that a new breed of powerful men had stepped in to replace the British, asked, “How happens this my friend? Is Joyce Junior no more?”[ix]

The desire to see Joyce Junior return to punish evil men continued into the 19th century. In a 1798 play titled, “The Tables Turned” one speaker opines that Joyce Junior should be placed in charge of a fleet that would sail around the world to “treat kings, and kingly government precisely in the same manner as he did the royalists at the commencement of our happy revolution.” In the mid-nineteenth century, with Boston having become an industrial city full of factories, one writer lamented that if Joyce Junior were still alive, he’d “groan” and “sigh” when seeing what his city had become.[x]

Who was Joyce Junior?

Who was Joyce Junior? According to a British officer stationed in Boston, the man behind the mask was the wealthy and handsome John Winthrop. The son of a Harvard professor, Winthrop was well schooled in Enlightenment literature, and, as such, would have loved to see the colonies independent of a distant king. Winthrop had financial reasons to resist the British, as well. Because he was heavily invested in a smuggling operation that provided Boston with Dutch tea, cheap English tea would hurt his bottom line. What better way to sell Dutch tea, than to attack duty collectors, promote boycotts, and threaten vendors selling English tea?

Joyce Junior may also have been one or more members of the subversive Sons of Liberty. Perhaps in an effort to draw attention to the character that he’d created, Sons of Liberty member Sam Adams wrote about the red-cloaked man in an article for the Boston Gazette in 1770. Adams was also known to use pseudonyms in his writing, so an alternate personality wouldn’t be out of character. The problem with Adams as Joyce Junior is that he was over fifty years old in 1774, hardly capable of dragging men from their homes and throwing them on to horse carts. If Joyce Junior were Adams invention, however, it didn’t necessarily mean that he was the man behind the mask. Another SOL member could have been the brawn to Sam Adams’s brain. Or the responsibility of riding as Joyce Junior fell to different people at different times.

There’s also the possibility that the various incantations of Joyce Junior—the red cloaked man, the masked leader of mobs, and the distributor of revolutionary handbills—were different men with unrelated goals. The people of Boston amalgamated anyone resisting the British into a single character, and, over time, multiple revolutionaries became Joyce Junior. As evidence for this conclusion, the handbills that appeared throughout Boston in 1774 seem to be from a much gentler person than the masked man who broke into duty collector’s homes and covered them in tar and feathers. After a particularly brutal attack on British duty collector John Malcolm, for example, a Joyce Junior handbill informed the public that the assault had not been his doing. This has led one historian to speculate that upper class revolutionaries co-opted the Joyce Junior identity in order to curb lower class mob violence.

Because there is so little information on Joyce Junior, any of these explanations could be correct. Or none. Until historians find a definitive answer, it may be best to think of Joyce Junior like V from V for Vendetta, an identity-less introvert driven to action by revolutionary ideals and a desire for vengeance. This may not be the most accurate characterization, but it’s certainly the coolest.

Brad Folsom

[i] Alan Moore, V for Vendetta. (New York: D.C. Comics, 1990). Much of the information from this article comes from Nathaniel Philbrick’s Bunker Hill. The book is excellent and should be read by anyone interested in the American Revolution. Nathaniel Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution (New York: Penguin, 2013).

[ii] The description of Joyce Junior’s mask comes from an 1821 description of Joyce Junior in the Boston Gazette. The writer describes the mask only as “horrendous.” I assume he wore an executioner’s mask because that’s what the real George Joyce wore when he executed King Charles I, but other historians assume the mask was a demon mask like those worn in Boston’s annual Kill the Pope Parade.

[iv] Boston Evening-Post, February 4, 1770.

[v] Boston Gazette, December 24, 1770.

[vi] Pennsylvania Gazette, February 2, 1774.

[vii] Boston Gazette, Wednesday, March 23, 1774; Essex Journal, March 28, 1774.

[viii] http://www.masshist.org/publications/apde/portia.php?&id=AFC02d169; http://www.masshist.org/publications/apde/portia.php?id=AFC02d165#AFC02d165n2;New-England Chronicle, Friday, May 23, 1777; Connecticut Gazette (New London, CT) Thursday, May 8, 1777 Paper: (Boston, MA)

[ix] Tar, Feathers, and… The New England Quarterly Vol. 76, No. 2, Jun., 2003.

[x] Boston Gazette, Monday, May 24, 1779 is one example of a newspaper reporting a Joyce Junior sighting.

In 1865, angry men carrying feathers and buckets of smoldering tar gathered outside the Greenwich, Connecticut home of interracial husband and wife, William and Betsy Davenport. Shouting racial epithets and rape threats, the mob beckoned for the Davenports to come outside. When, instead, William’s elderly mother called out of a window for the men to go away, the mob grew angry, threw rocks at her, and tried to break into the house. This prompted the old woman to grab a gun. The events that followed left one man dead and would contribute to a change in political discourse in the United States. Here’s the story as it appeared in the August 8, 1865 edition of the New York Tribune:

RIOT AT GREENWICH, CONN.

Marriage of a Colored Man with a White Woman

Attempt to Tar and Feather Him.

A RETURNED VETERAN SHOT DEAD

The little town of Greenwich, Conn., has been thrown into a perfect fever of excitement in consequence of an affray between a party of whites and a colored man named Henry Davenport, in which a recently discharged soldier was instantly killed.

The circumstances, we are informed are as follows: two years ago Henry Davenport, a man well known and esteemed by his neighbors for his marked probity of character, wooed and won the affections of a white damsel, and in due time the twain were made one flesh. It roused the ire of some of the indignant villagers that a white woman should so far forget her honor and her race as to ally herself with one of the hated sons of Ham, and soon after the marriage, frightened by their threats be removed to New York. A few weeks ago, thinking that the affair had blown over, they returned to their home. When this became known, the villagers prepared to carry their old threats into execution.

Accordingly on Saturday night, a motley crowd proceeded to visit his dwelling with the intention of administering to him a coat of tar and feathers, while against his wife many threats too vile for repetition were expressed or darkly hinted at.

Upon reaching the house they found Davenport and his family had retired. In response to their knocks his mother, a very old woman, rose and asked what they wanted. They answered “Some ice cream.” Upon being informed that none was to be had, the demanded that Mr. Davenport and his wife should confide themselves to their tender keeping. Upon this being refused and the men warned away, they immediately commenced stoning the house and endeavoured to break in the door, yelling “Drag her out,” “Kill the nigger,” “Roast them,” etc., etc. Becoming seriously alarmed, the old woman requested her son to hand her the musket, which was, in fact, a blunderbuss of the most antique pattern. This she protruded from the window and threatened to fire but the only answer was a shower of stones.

She fired two shots, the first being harmless, the second taking effect upon a returned veteran named Ludd Shale, who was almost instantly killed. This sobered the rioters, and they beat a hasty retreat, making no further demonstrations. Davenport was immediately arrested, a jury impaneled, and every effort made to impute blame to him and to his family for the past they had enacted, but without success.

Yesterday afternoon the jury returned a verdict of “justifiable homicide,” and Davenport was released from arrest. While the friends of the deceased swear vengeance against him, the utmost excitement prevails (the town being about equally divided in relation to Mrs. Davenport’s justification or nonjustification of the homicide) and there has been, we learn, no little effort to make political capital out of the unfortunate affair.

Mrs. Davenport informed our reporter that if they hang her husband she would marry the blackest man in the State of Connecticut that would have her.

The shooting sparked a national debate on interracial marriage, specifically interracial marriage between a black man and a white woman. Although the Civil War and the recently passed Thirteenth Amendment had determined the United States would no longer permit African slavery, the status of blacks in American society remained undetermined in 1865. Would the U.S. deny former slaves the right to vote or even deport them to Africa or Latin America as many northern Democrats and former slave-holding southerners hoped? Would blacks receive full citizenship as most in the Republican Party wanted? Would race cease to exist in the eyes of the government, meaning that whites and blacks could marry with impunity?

Excepting a handful of forward thinking abolitionists, before the Civil War, Americans detested the idea of interracial marriage. Although all humans have innate biases against those they deem as “others”–persons with different religious beliefs, nationalities, languages, ethnicities–Antebellum white Americans were particularly fixated on skin color. Historians have debated the reasons for this extreme racism, but most agree that it had a basis in slavery. The first English colonists who used African slaves in America made money, but because slavery was at first an illegal and socially unacceptable practice, in order to continue profiting from unfree black labor, whites dehumanized blacks. By portraying blacks as intellectually inferior, violent, and animalistic, it made slavery seem less severe and allowed for the legalization of the practice. Over time, as slavery became institutionalized, free whites gained educational and economic advantages over black slaves, furthering the perceived differences between the two races.

Because of this growing perception that blacks were an inferior subset of humans, interracial unions came to be seen as unnatural, and by the 19th century, most U.S. states had outlawed the practice. Hoping to benefit from this negative perception, opponents of anti-slavery Republican Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 and 1864 presidential elections attempted to place the candidate among the fringe abolitionists who supported interracial coupling. In the 1864 election, for example, Democrats released a pamphlet purporting to be Lincoln’s post-war plans for nationwide miscegenation. Although revealed to be a fake, many in both the North and the South feared that once the Civil War was over, interracial marriage would be commonplace.

Miscegenation Ball. An 1864 cartoon playing on fears that Lincoln’s election would lead to interracial coupling.

The Davenports’ relationship seemed to confirm this suspicion to the people of Greenwich, Connecticut. In the aftermath of the attack on the Davenports’ home, the Republican-friendly New York Tribune labeled Greenwich a “copperhead” city—copperheads were pro-South, anti-black, northern Democrats—but this wasn’t the case. Although surrounded by counties that voted Democrat in the 1864 election, Greenwich was a part of Fairfield County, which went for Lincoln. This likely meant that most in the Greenwich were anti-slavery and that at least some believed in citizenship for blacks.

In spite of these progressive beliefs, half of Greenwich’s residents blamed the Davenports for the riot outside of their home, not the men who made up the mob. Their decision to marry, in spite of society’s objection to miscegenation, was to blame for the disturbance. Although Greenwich jurors felt that, by law, Henry Davenport’s mother was justified in shooting the man who attempted to break into her home and therefore acquitted her and her son of legal wrongdoing, the jury didn’t countenance interracial marriage in their community. After the trial concluded, a juror named Philander Button, a Republican and supporter of black citizenship, berated Davenport’s “very improper conduct.” He informed Davenport that Greenwich was a moral community and instructed the man to take his wife and leave town.

Newspapers throughout the Unites States published Button’s comments to Davenport. Most, even those with Republican leanings, agreed with Button’s assessment of interracial marriage and the juror became a minor celebrity for a brief time. Although the Republican editors of the New York Tribune tried to take Button to task for what they saw as hypocrisy and colorphobia, they, too, disagreed with the couple’s decision to marry and wilted when rival newspapers accused them of supporting interracial marriage. Apparently, Republicans wanted equal rights for blacks, unless it meant black men sleeping with white women.

Whereas before the Civil War, black men were not in a position to threaten the white male role of protector and progenitor of white women, the possible inclusion of black males into American society meant that white males would have new sexual rivals. Rivals that because of institutionalized racism, they saw as inferior, animalistic, and violent. This perceived threat added psychological, sexual elements to the public discourse that had not been present before.

Democrats took note of the Republican reaction to cases like the Davenports. Following the Civil War, the Democratic Party was in a position of weakness. Because it had been southern Democrats who’d seceded from the Union, many northerners refused to vote for their party. To make matters worse, if Republicans had their way, blacks would be given the right to vote, meaning they would inevitably vote against the party of their former enslavers. With much of the nation turned against them, and with the prospect of Republicans growing stronger, the Democrats needed a sneaky tactic to survive as a party. They needed a “straw man.”

Politicians have used straw men for centuries. Essentially, the straw man tactic is when someone uses fallacies, stretches in logic, and emotional rhetoric to misrepresent an opponent’s position. In a straw man argument, if Person A says children shouldn’t be allowed to eat ice cream, Person B would counter that because ice cream makes children happy, Person A hates children because he doesn’t want to see them happy. It doesn’t matter that Person A is concerned about childhood diabetes. In a straw man argument, the discussion ceases to be about the true issue—the emotional benefit of ice cream v. the health detriments—and instead becomes Person A hates children and Person B wants them to be happy.

Because, as the Davenport case makes clear, even ardent supporters of black equality were uneasy about the prospect of black men marrying white women, Democrats realized that they could divide the Republican Party by associating black citizenship with interracial marriage. They could turn public opinion or scare moderate Republicans into voting with Democrats. One historian remarked that from 1866 forward, “the Democrats injected the cry of amalgamation into every conceivable debate, no matter how irrelevant it actually was.” In typical straw man fashion, Democrats misconstrued the main post war issue from “what makes a U.S. citizen” to “would you marry your daughter to a nigger?”

1868 Harper’s Weekly cartoon mocking Democrats who used the threat of miscegenation in political debates.

Democrats brought this line of argument to the 1866 congressional debate over the 14th amendment—which would grant blacks equal citizenship and guarantee protection of their civil rights. Democrats argued that because marriage was a civil right, a national amendment protecting civil rights would supersede state laws against interracial marriage. Any congressmen approving the amendment would, in effect, be removing one of the few barricades preventing black men from taking white brides.

The argument proved effective, as many voters made the connection between miscegenation and black citizenship. Unable to obtain enough support for the amendment with votes from southern states, northern Republicans passed the Reconstruction Acts, which removed southerner representatives from Congress and placed the South under military rule. Only after these states were removed from vote tallies were Republicans able to ratify the 14th Amendment.

The ratification of the 14th amendment didn’t stop Democrats from using miscegenation as a scare tactic. When Republicans introduced the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which would require businesses that served the public to provide blacks with equal treatment, again, Democrats asked, if private businesses couldn’t take race into consideration, wouldn’t this eventually lead to private individuals being forced to ignore race in their personal lives? If so, would white women be committing a crime for rejecting a black suitor based on race?

At first, Republicans tried to laugh off the ludicrousness of the argument. One representative sarcastically proposed that white woman be fined for refusing a black man’s marriage proposal. Another joked that if “a Negro married a white woman, the Negro would get the worst of the bargain.” When these attempts at humor fell flat, Republicans attempted to portray southerners as hypocrites for their history of sleeping with female slaves. When this also failed to show reluctant Republicans the fallacy of the Democrat argument, party leaders asked many of their recently elected black representatives to stand before Congress and promise that they didn’t seek miscegenation or social equality, just political equality. Only after this humiliating show did the Civil Rights Act of 1875 pass.

This would be the last time Republicans would be able to overcome the miscegenation straw man. In 1877, after the U.S. military ended its occupation of the South, southern leaders instituted measures to prevent blacks from voting. This decreased Republican representation in Congress, which meant they no longer had the numbers to make up for those influenced by the Democrat’s miscegenation argument. Because public sentiment on interracial marriage remained the same well into the twentieth century—only 4 percent of whites supported interracial marriage in the 1950s–the straw man continued to be used into the twentieth century. For example, on the issue of integrated schools, a topic of political debate in the 1950s, Jackson, Mississippi’s Daily News, opined that, “white and Negro children in the same schools will lead to miscegenation. Miscegenation leads to mixed marriages.” Voters bought this argument and refused to elect those seen as supporting mixed marriages.

With Congress deadlocked by this historical, sexual racism, blacks lost many of the rights they’d gained following the Civil War. It would not be until after a progressive, lifetime-appointed Supreme Court ruled in Virginia v. Loving in 1967 that laws against interracial marriage were unconstitutional that the white American public would overcome its opposition to mixed race marriages. Whereas 90 percent of Americans opposed interracial marriage in 1865 and 1965, by 2011 that number had reversed to 86 percent supporting such unions. Perhaps ironically, the Supreme Court based its Virginia v. Loving decision on the thought that marriage was a civil right. Because the 14th amendment said that governments could not deny civil rights based on race, the Supreme Court ruled that interracial marriage laws were unconstitutional. So it turned out the Democrats in 1866 were right in theory, just wrong in principle.

Brad Folsom

Sources:

Alfred Avins, “Anti-Miscegenation Laws and the Fourteenth Amendment: The Original Intent” Virginia Law Review , Vol. 52, No. 7 (Nov., 1966), pp. 1224-1255

New York Tribune