On April 1, 1895, American businessmen, Mexican elites, local officials, soldiers, vaqueros, and vendors selling cold drinks filed into the Plaza de Toros bullfighting arena in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. Sitting just across the border with the United States, the bullring had been prepped for a spectacle. Red, white, and green Mexican flags hung throughout the arena, as did the smell of sweat and manure. It was hot, and those unable to afford a seat in the shade suffered in the desert sun.

The unpleasant heat and smell did little to dull the excitement of the coming event. The people in the arena were about to witness a never before seen event. Something reminiscent of the days of Ancient Rome. The crowd was about to watch two of the largest mammals on earth face off in a steel cage match. An American grizzly was going to fight an African lion.

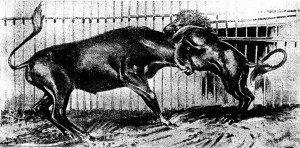

The 700-pound American grizzly sat in the center of the bullring, confined within a fifteen-foot high, thirty-foot wide steel cage draped in canvas. The bear’s opponent, a 550-pound African lion was locked in a pen outside of the arena.

When the designated fight time arrived, the lion’s owner used pokers to prod the lion out of his pen and into a portable cage, which he then wheeled into the bullfighting ring and placed flush against the entryway to the bear’s cage. The crowd gasped audibly upon viewing the jungle cat for the first time, most having never seen such an animal before. The lion broke the silence with a loud roar, which the crowd met with cheering and hollering. When the canvas was removed from the fighting cage, revealing the lion’s grizzly bear opponent, the spectators grew louder. The noise and the sight of the boisterous audience agitated and scared both caged beasts. They wanted to take out their anger and fear on anyone or anything that they could get their paws on.

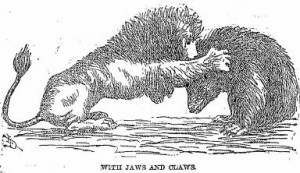

When a trainer opened the door separating the two animals, the lion immediately leapt fifteen feet into the air and came down directly on top of his grizzly opponent. The bruin, standing on his hind legs, caught the lion as it landed and used his forepaws to hold the cat’s teeth away from its neck. The bear could do nothing, however, to stop the lion’s claws from tearing into its midsection. Fur and blood flew everywhere.

Fortunately for the bear, its thick hide prevented the lion from reaching vital organs. Unfortunately, the grizzly was slow and every attempt to bite and claw the lion failed. The jungle cat was simply too quick. To those in attendance, it looked like the lion would eventually wear down the bear with its claws.

After the animals held their upright position for nineteen minutes, the grizzly realized that it was much stronger and heavier than its opponent. Using its powerful arms, the bruin grabbed the lion and squeezed with all of its might. The beast then created torque with its powerful back and tossed the jungle cat into the air, the lion turning a complete somersault before landing on its feet in the center of the cage. The fight was on.

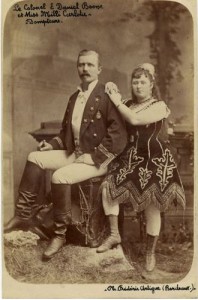

The two animals belonged to Colonel E. Daniel Boone, great grandnephew of American frontiersman Daniel Boone. Boone was a likeable man who got along well with just about everyone. An animal trainer, Boone had come to Mexico out of desperation. His lion had just killed a man, and he needed to get rid of it. Boone also needed money. He hoped to solve both problems with his animal cage fight.

Like his great granduncle, Boone had led an interesting life. Born in Kentucky and raised in Louisiana, Boone served in the Confederate army during the Civil War, earning the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. After the war, Boone joined a group of Americans who landed in Cuba to support the island’s revolution against Spain. From Cuba, Boone traveled to Peru, where he served as a military adviser. He then went to Algeria, where he fought with the French Army against a local insurrection.

During his time in Africa, Boone became acquainted with lions and began training the animals for show. Although the details of his early lion taming days are lacking, Boone became famous for putting his head in a lion’s mouth. He soon began to take the animals to different ports to show off his tricks. His training skills grew over time and word spread throughout Europe and Africa that an American could make the King of the Jungle do whatever he pleased. Boone even came to the attention of the Sultan of Turkey, who, after witnesses one of the trainer’s lion shows, hired Boone to serve in the Turkish army.

After his time in Turkey, Boone returned to Africa and began to search the continent’s interior for lions to sell to circuses in the United States. Although a dangerous job—a wounded lion almost killed Boone in one instance—the trainer soon had a surplus of lions and began training the animals in order to sell them to American circus owner P.T. Barnum. In total, he captured, trained, and sold 130 African cats. After living briefly in London, Boone got married and his wife joined him in training lions. She even performed Boone’s head in the lion’s mouth trick. The couple had two children.

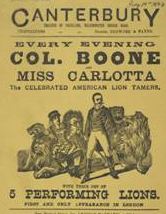

In 1891, the Boone family and their trained lions sailed to the United States where they traveled the vaudeville circuit as performers in the Adam Forepaugh Circus. By 1893, Boone had enough money to open his own vaudeville show.

To entertain crowds that often numbered in the tens of thousands, Boone had his lions ride tricycles, play on seesaws, and hold ropes for dogs to jump over. Over time, he added wolves, bears, gorillas, monkeys, leopards, and tigers to his stable of acts. Although Boone would continue to be the main lion tamer, he also hired attendants to train and care for his animals. Newspapers throughout the United States lauded Boone’s shows, calling them “the most astonishing exhibition of man’s supremacy over the brute creation.” This wasn’t hyperbole. Boone’s animal show rivaled or surpassed all others on the vaudeville circuit.

Although critically successful, the animal show was plagued with problems. Once, when Boone changed clothes between performances, one of his lions got confused, thought Boone was a stranger, and tackled him. The trainer managed to calm the lion before he was hurt, but in another instance, an angry cat forced Boone to flee from the cage. Boone was lucky. One of his trainers would not be.

Boone took his animal exhibit to the San Francisco Midwinter Fair in January 1894. Everything proceeded like normal for the fair’s first two weeks, but during a performance on February 14th, there was a power outage while attendant Carlo Thiemann was repairing the lights in the lion cage. During the blackout, a 550-pound male named Parnell, likely scared by the crowd which had become noisy during the blackout, leapt on Thiemann and began clawing and tearing at his body. The two other lions soon joined in on the assault. Boone reacted quickly, grabbed a lion prod, entered the cage, forced the animals away from the attendant, and dragged the man to safety. In spite of the hasty rescue, Thiemann had lost too much blood by the time he arrived at the hospital and died of his injuries.

Two days after the incident, Boone honored the attendant by holding a dramatic funeral. Dressed like Indians, Mexicans, and Arabs, the members of the circus surrounded the Thiemann’s casket, while a band played a funeral dirge. Boone also brought his lions to the funeral, and they growled during the entire affair to the discomfort of many in attendance.

The death of the trainer put Boone in a predicament. He didn’t know what to do with the lion pack leader, Parnell. Although raised in captivity, Parnell had a reputation for viciousness. During one show, Parnell grabbed one of Boone’s favorite dogs and began to tear into the animal. Boone attempted to scare Parnell into letting the dog go by firing his pistol near the lion’s head, but it was to no effect. Parnell only released the half-dead dog when Boone grabbed a heavy iron bar and prodded the lion.

Boone tried to continue using Parnell after Thiemann’s death, but the animal’s reputation for violence scared away ticket buyers. Many in San Francisco called on the trainer to euthanize the man-killing animal. By March, Boone realized that he could no longer use Parnell in his shows. He would have to get rid of the lion one way or another. Thing was, lions were expensive–Boone estimated that the animals cost over $5,000–and so the trainer didn’t want to waste Parnell’s life if there was a profit to be made.

By spring, 1894, Boone had begun to go broke. It seems that he had expanded his circus too quickly. Perhaps the lion tamer had not realized that as the number of animals in his traveling show grew, so did his bills. Animals have to eat and food costs money. Trainers, ticket takers, and attendants also needed pay. It’s also possible that Boone’s financial woes owed to his gambling. The colonel rarely turned down a bet.

Needing cash and unwilling to euthanize an expensive animal, Boone came up with a plan: he’d put on a death match between Parnell and an American grizzly bear. In the history of the world, such a fight had never happened. When the continents separated millions of years in the past, the two species had not existed in their current form. The first time they’d face off, then, would be under Boone’s direction.

It’s impossible to know where Boone came up with the plan. Although the Ancient Romans had staged hundreds of interspecies fights—including fights between lions and European grizzlies—the practice of pitting two different types of large mammals against one another wasn’t common in modern times. It was too expensive. As Boone well knew, getting a lion from Africa was a costly endeavor. Bears cost money too. You had to pay handsomely to make men risk their lives catching the animals.

Although expensive, interspecies fights did take place in rare instances in modern times. In Paris in 1893, a showman had staged a fight between a polar bear and an African lion, with the jungle cat easily besting his larger opponent. Perhaps Boone had read about this epic encounter when deciding to stage his own, Americanized, version of the fight. Boone may also have developed the idea of fighting a lion and grizzly of his volition. He had bears in his show, and people must have asked which of his animals was the toughest from time to time.

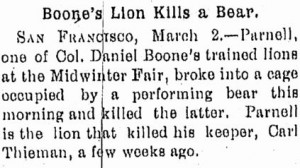

Parnell may have spurned the idea of fighting a bear himself. On March 2, 1894, a California newspaper reported that one morning the lion escaped his cage, somehow gained entry into the pen of a small performing bear, and killed the animal. This implausible scenario, if true, would have certainly given Boone a reason to think about pitting a larger bear against Parnell.

Regardless of the origin of the idea, Boone knew that a fight between an African lion and an American grizzly would make money. To make this money, however, Boone had to invest a significant amount of capital to prepare for the event. He needed a venue, so he rented the midway of the San Francisco fairgrounds—ironically, the very fairgrounds where Parnell had killed Thiemann. He also paid for the construction of a steel cage and stands and bought ad space in newspapers throughout California. The event’s biggest expense, however, would be providing an opponent for Parnell.

Accounts of the bear’s origins differ. Most sources agree that the animal was a North American Brown Bear, also known as a grizzly or silvertip bear. Some sources place the bear’s birthplace in California, others the Rocky Mountains. The grizzly weighed around 700 pounds, average size for brown bears. Like all grizzlies, the bear had razor sharp claws and teeth, a trait developed for tearing apart prey like moose, elk, bison, and smaller black bears. (It’s possible that Ramadan was one of the last remaining California Golden Bears, a subfamily of grizzlies that went extinct in 1922. If this were true, then Ramadan would not only be the first American grizzly to fight a lion, but also the last California Golden Bear to do so).

It’s unclear where Boone found the bear. The trainer may have taken the grizzly from his own cadre of trained animals. One newspaper reported that the animal was relatively gentle, raised in captivity, and had never killed another living creature—indicating that the animal belonged to a traveling show. A second account says that the bear had been captured in the wild, also plausible because the animal is often said to be from California, where Boone was planning to hold the fight. He could have requisitioned a hunter to find an animal for him. Perhaps the most intriguing tale of the grizzly’s origins holds that Boone bought the bear from a circus in New Orleans at a discount. The animal was so cheap because it had recently killed two of its trainers and, like Parnell, faced euthanization for its actions. If true, the fight would be between two man killers.

However he acquired it, when the bear came into Boone’s possession, he began calling it Ramadan, a reference to the Muslim holy month.

Boone planned to stage the fight between Ramadan and Parnell on April 21, 1894. The showman took preorders on tickets, charging 20 dollars apiece. Although this was a substantial sum of money in 1894, San Francisco in the late 1800s was home to a number of wealthy merchants who could afford the high price tag. As soon as Boone announced the fight, tickets began “selling like hot cakes,” one newspaper reporting that within a week of advertising the event had sold over 1,000 seats.

Local editorialists mocked the upcoming event, comparing it to the Roman spectacles put on by the maligned emperor Nero. The high ticket prices particularly irked one columnist, who lamented that society had degraded to a point where people refused to pay 10 dollars for an opera or a play, but would put up twice that amount to see two four-footed brutes scrap. The columnist closed his editorial by asking sarcastically, “Who says we are not living in an intellectual, refined age.” A third writer condemned the proposed event, but couldn’t resist betting on the bear to emerge as the contest’s victor.

Newspaper writers were not the only ones opposed to Boone’s upcoming show. A group called the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) began petitioning the mayor of San Francisco to put an end to the event. Made up of animal lovers who abhorred violence to creatures incapable of defending themselves, the ASPCA was a powerful nationwide lobby that had supporters in Washington. The mayor of San Francisco, not wanting to earn the wrath of the ASPCA, and sympathetic to their cause ordered the local police to the Midwinter fair grounds to tear down the animal fighting arena. Unfortunately for Boone, he lost the money he had invested in the show and was forced to refund sold tickets.

Undeterred, Boone decided to move the fight out of county to the Vallejo Race Track. The event was to be held on July 4th and was expected to draw 20,000 spectators. Once again, however, the proposed event was canceled, this time for unknown reasons. Perhaps the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals caught the governor’s ear and had him outlaw the fight throughout California.

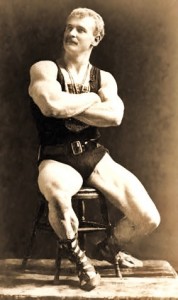

To recoup some of the money spent advertising the bear versus lion showdown, then, Boone arranged for famed strongman Eugene Sandow to fight a small lion, advertising the event as “man vs beast.” The show was a dud. The lion appeared lethargic in the ring and had had its claws padded and its mouth taped to avoid injuring Sandow. The strongman did the best he could to elicit excitement from the crowd, at one point picking up the lion, swinging it, then pinning it to the mat, but the lack of true danger left the crowd disappointed. Many demanded a refund on their ticket prices, putting Boone further in the financial hole.

Unable to find a venue for Parnell and Ramadan’s bout in California, Boone packed up his animal show in late 1894 and moved across the United States. He tried to fight the animals in Fort Worth, but a judge deemed the exhibition too risky to spectators. In March 1895, the circus arrived in Laredo, Texas. There Boone made the decision to transfer his interspecies fight across the border to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico where there was no Mexican Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals to stop the show.

Boone rented out the Plaza de Toros bull-fighting ring in Nuevo Laredo to host the fight. Although the biggest arena in the border town, the Plaza de Toros could only seat 650 people, much fewer than would have been in attendance if the fight had been held in San Francisco. Boone had no other option, however, so he oversaw the construction of 15 foot high, 20 foot wide steel cage in the center of the bullring. He also sent notice to local newspapers that he was putting on a fight to the death between an American grizzly and a lion.

Unfortunately for Boone, he would be unable to fill even the meager capacity afforded by the Plaza de Toros arena. Most newspapers in Mexico and the U.S. refused to publish news of the fight, thinking something so ridiculous must be a joke. It didn’t help that Boone had scheduled the bout for April Fool’s Day. Also, it seems that Boone kept ticket prices the same as they had been in San Francisco. Whereas people in wealthy San Francisco could shell out twenty dollars for a trivial event, the people of poverty-stricken Mexico and South Texas had no such disposable income. There would be plenty of empty seats for the showdown between Ramadan and Parnell.

When Boone’s long planned event finally took place on April 1, 1895, it was in front of a sparse, but eclectic crowd of Mexican politicians, businessmen from the United States, and a handful of ranchers that had scrounged up enough money to pay for the costly tickets. A few workers selling confectionaries, attendants working the show, and some poor locals who snuck into the event were also in attendance.

Economic and national background faded away when Parnell was wheeled into the arena, the lion having been kept outside the stadium until the fight began. Ramadan was in the center of the bullring in the fight cage, isolated from the crowd by a canvas covering. The draping was removed only after Parnell’s transportable cage was placed beside Ramadan’s. The two animals reacted excitedly upon seeing one another. They were scared from the noises and mass of humanity and were prepared to fight.

Ramadan sat on his hind legs opposite the cage from the entryway. When an attendant opened the trap door separating the two animals, Parnell sprung into action. Leaping fifteen feet into the air, the lion spanned the length of the cage and came down on Ramadan. The grizzly, however, managed to stand on his hind legs and extend his forepaws to stop the lion before he could sink his jaws into his throat. The two animals held this upright grappling position, Parnell scratching and clawing at Ramadan’s thick hide, while the grizzly did his best to hold off the lion. The bear was unable to do any damage on his opponent, while the cat successfully used its claws to rip chunks of flesh from Ramadan’s underbelly. Blood and fur carpeted the cage. If not for the bear’s thick hide, Parnell would likely have released Ramadan’s internal organs, putting a quick end to the fight. Finally, after nineteen minutes the combatants fell to the ground.

Parnell stood up and began sniping at Ramadan, the grizzly unable to bring his claws or teeth to bare on the lion. Every time the bruin lunged at the African cat, the more agile lion simply sidestepped and swiped at his opponent. When Parnell came in for one of his strikes, the bear stood on his hind legs and once again grappled the lion. This time, however, Parnell got past the bear’s forepaws and sunk his teeth into the animal’s neck. Ramadan responded by using his brute strength to hug the lion. Shocked by the bear’s strength, Parnell let loose his bite, allowing the grizzly to tackle and mount his opponent. Although Parnell escaped before the bear could do any damage, Ramadan had clearly found a way to defend himself.

The two animals circled one another in the cage before Parnell once again pounced and sunk his teeth into Ramadan’s neck. Again the bear responded by hugging his opponent with all his might. The lion’s teeth sunk deeper. In response, the grizzly’s grip grew tighter. To those in attendance it was unclear which of the beasts would give in first. Then, without warning, the lion let go and bellowed out a roar of pain, the bear’s hold so tight that one observer remarked, “I could almost hear the bones cracking.” Ramadan then grabbed Parnell with “a beautiful half Nelson that would have done credit to a professional wrestler” and hurled the lion.

Parnell turned a complete somersault in the air before landing on his feet in the center of the cage. Recovering quickly, the lion circled and attacked Ramadan from the rear. The bear, showing agility not seen up to this point, turned, grabbed the lion, and lifted him into the air. With Parnell’s head dangling, Ramadan began squeezing and shaking the feline as if it weighed the same as a house cat. Ramadan then lifted his opponent into the air and threw him against the side of the cage.

Parnell’s head struck a steel bar with a thud, and the lion collapsed to the ground. He remained unconscious for over a minute before slowly getting to his feet. Although the lion again attempted to attack Ramadan, it was clear that he had little fight left in him. He was slow and struggling to walk. Ramadan appeared to be done fighting, as well, choosing to parade around the cage instead of continuing the battle. After thirty-three total minutes in the cage, Parnell collapsed to the ground and refused to get up. He was exhausted and possibly suffering from broken ribs and internal bleeding. The fight was over.

The crowd, promised a fight to the death by Boone’s advertisements, started booing. Although they had just witnessed an epic encounter in which both animals put up a spectacular fight, the multitude wanted blood. Under pressure from the crowd, ringside attendants attempted to restart the fight by prodding Parnell with metal poles and hot irons. The African cat, however, had had enough. He was done. No amount of cajoling would get him to take on that grizzly again.

Denied the death that they’d grown to expect from years of watching bull fights, the largely Mexican crowd began jeering and throwing things at Boone, demanding their money back in a flurry of Spanish epithets. Fearing that a riot would break out, Mexican police officers placed Boone under arrest for false advertising. They escorted the showman out of the arena, placed him in the local jail, and demanded that Boone refund the crowd’s money before they would release him. It appears that the lion tamer complied with the request. For all of his efforts Boone had made no money.

Newspapers throughout the United States reported on Parnell and Ramadan’s epic bout. A journalist from Laredo had attended, and papers everywhere reprinted his detailed account of the battle. An artist’s rendition of the event also found significant coverage. Most newspapers reported that the grizzly had been the victor, but others said the bout was a draw. People demanded to know more about the fight.

Boone decided to capitalize on the event’s popularity. Shortly after the fight, he announced that Ramadan would face a Mexican bull named Panthera from the famous Las Cruces ranch. It’s unclear why Boone decided to pit Ramadan against this specific animal, but it wouldn’t be hard to imagine that a local offered up the animal as an opponent for the bear, and Boone, seeing a chance to recoup his money accepted the challenge.

A product of thousands of years of selective breeding, Panthera was essentially a human creation. He was massive, weighing some half a ton, much heavier than cattle in the wild. Panthera was also more aggressive than other cattle. His ancestors had been used to fight humans, rhinos, elephants, and other animal combatants in the Roman coliseum. The Romans and later the Spanish had chosen the most violent and successful of these bulls to breed and over time they created animals like Panthera. Animals whose sole purpose was to bring harm. And Panthera could bring harm, especially with the long, sharp horns that protruded from his skull.

Ramadan would be giving up the weight advantage that he had held in his fight with Parnell. He would also have to adjust to a different cage size, as the cage’s diameter was increased from 20 to 30 feet to allow the bull more room to maneuver. Ramadan still held a number of advantages over Panthera, particularly when it came to close combat. He had more weapons than his bovine opponent–the bull had only his horns and head, the bear had four claws and a vicious set of teeth.

The bout between Ramadan and Panthera was set for April 14th. In the two weeks leading up to the event, the fight took on nationalistic overtones. Those on the United States side of the border backed the American grizzly Ramadan, while Mexicans favored the Mexico-born Panthera. Bets on the winner were as large as 100 dollars. The event sold out quickly with half the 650 available seats going to persons from Mexico, half to those from the United States.

The fight between Panthera and Ramadan took place on April 14, Easter Sunday. The sold out crowd cheered as Panthera was brought into the cage at 3:30 P.M. The animal appeared ready to fight. Its tail lashed in the air, and it lunged any time someone got close to the cage. Photographers, with their constant flashing, especially irked the bull. On more than one occasion, Panthera bent the cage’s bars when attempting to ram a photographer.

Ramadan was wheeled into the arena at 4:45 P.M. and was met with enormous cheers from the Americans among the crowd. As the bear came closer, Panthera began ramming his cage in anticipation of the fight ahead. In order to allow Ramadan a safe entry into the cage, then, it was necessary for a bullfighter to go to the opposite end of the arena and distract Panthera. With the bull occupied, Ramadan was allowed to enter the cage unmolested. He headed in the direction of Panthera.

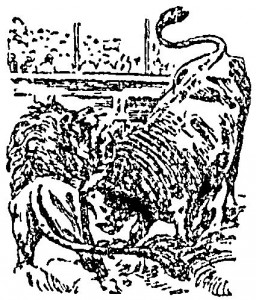

When the bullfighter backed away from the cage, Panthera turned to find that a strange hairy creature was heading in his direction. Before the bear could close any more distance, the bull lowered its head and ran directly at his opponent. Never having seen an animal this large, nevertheless one heading straight for him, Ramadan grew confused and turned to one side, opening himself up to a direct charge.

Panthera drove one of his horns full speed into Ramadan’s shoulder, goring the bear. Ramadan howled in pain. Confused and unable to grab the bull as he had done with Parnell two weeks before, Ramadan began running in circles around the cage. Panthera pursued until he backed Ramadan against the bars, trapping his opponent. When the bull went in for a second charge, Ramadan swiped viciously, managing to drive the bull back temporarily. The bear then used the opportunity to retreat to the other side of cage, but he was confused, hurt, and didn’t want to fight anymore. He wanted out.

To the shock of everyone in attendance, Ramadan wrapped his claws around the cage bars and started climbing to freedom. In an instant, the bear scaled the fifteen-foot cage and pulled himself to the edge of the ring. He was about to jump into the open arena.

The sight of a bleeding, angry bear sent the crowd running for the exits. People who hadn’t exercised since childhood found themselves on their feet, trying to push their way to safety. Those at the top of the bullring prepared to leap the twenty-five feet to the ground outside of the arena. For some reason—one newspaper speculated that the bear didn’t want anyone to lose their life in the scramble—Ramadan abandoned his escape plan and lowered himself back into the cage with Panthera.

The climb and the loss of blood from Panthera’s first charge took its toll on Ramadan. He sat on his haunches and refused to fight. The bull, likewise, didn’t seem interested in opening himself up to another bear attack. In order to get the fight started then, a bullfighter went to the cage behind Ramadan and waved a red bag in an attempt to draw Panthera’s ire. It worked, and the bull charged. Ramadan saw his opponent’s approach and attempted to raise himself up for an attack. He was too slow. Panthera drove directly into Ramadan’s side. The bear responded by swiping his claws across the bull’s head. He then retreated to the other side of the cage.

When Panthera once again approached, Ramadan was ready. He reared up and clawed the bull about the neck and head. The grizzly then went to bite the bull’s jugular. Unfortunately for the bear, Panthera was raising his head at the moment of attack, and one of the bull’s horns pierced the bear through the cheek. Blood began to flow from Ramadan’s mouth. Panthera took the opportunity to charge the bear, ramming the animal so hard that Ramadan’s feet left the ground.

Ramadan couldn’t mount a comeback. He just laid there while Panthera took potshots at him. Wanting to avoid the inconclusive end of the previous fight, trainers prodded the grizzly until he half-heartedly went after the bull. The attacks had no force behind them, and Ramadan continued to lose blood. He labored around the ring breathing heavily, until after almost an hour of constant punishment, the mighty grizzly put his head on the ground, closed his eyes, and died.

Again, newspapers throughout the United States reported the events on the border. Although some among the crowd complained that the bout was lacking in action, they had no reason to demand their money back. Boone had finally made money off of an animal fighting event. Overall, however, he was still in the hole. So in last-ditch effort to recoup his loses, Boone scheduled a third bout. This time Parnell would take on Panthera, completing the king of the beasts trifecta.

Boone had contemplated replacing Parnell, fearing the animal had yet to recover from his fight with Ramadan two weeks before. To test the feline, then, Boone put a goat in his cage. Parnell, showing no signs that a grizzly had recently tossed him around a steel ring, leapt on the goat, tore it to shreds, and ate it. A few days later, anticipating the upcoming bout with Panthera, Boone put a young steer in with Parnell. The bull didn’t last long. The lion tore open its throat and made it a meal.

It was apparent that Parnell was still vicious, something that George Rooke, a trainer who had accompanied Boone on his trip to Laredo, found out the hard way. Shortly before the scheduled fight with Panthera, Rooke stood too close to Parnell’s cage. With no warning, the lion leapt forward, grabbed Rooke by the arm, and dragged him against the cage, trapping the trainer’s shoulders between two bars. Unable to get free of Parnell’s grip, Rooke screamed and then fainted. Meeting no resistance, Parnell used his teeth to rip the man’s bicep from his arm. His follow up bite broke bone. The lion let up only after those around the cage began beating him about the face with crowbars.

Boone immediately took Rooke—his arm hanging on by only tendon and flesh—to a nearby hospital. The severity of the injury forced the doctors to amputate the trainer’s arm. Likely owing to the unsanitary conditions in 1890s hospitals along the U.S.-Mexico border, there were complications with the surgery. Rooke developed something that local newspapers called “poisoned blood.” The trainer was unable to fend off the bacterial infection, or whatever it was, and died shortly thereafter. Parnell’s body count was up to two.

News of Parnell’s vicious attack and nationalistic enthusiasm for the Mexican bull Panthera created a large demand for a third fight. Also adding to the appeal, Boone heavily advertised the upcoming fight in newspapers in the U.S. and Mexico. Realizing that he could sell more tickets if he moved to a larger venue, Boone rented a bullring 100 miles south of the border in Monterrey, Mexico. The new arena had 2,000 seats, all of which sold out for the upcoming fight.

When the fight day arrived on April 21st, Panthera once again appeared ready for battle, showing no sign that the injuries sustained in his fight with Ramadan would affect his performance in the cage. As the bull paraded about the arena, the mostly Mexican crowd cheered their champion. The spectators met Parnell’s entrance into the arena with boos.

The fight started in much the same way as Panthera and Ramadan’s bout. The bull charged the lion, intending to gore it, as he had done with the bear. But Parnell was much quicker than Ramadan. He quickly moved out of the way of Panthera’s horns. The bull continued to charge but Parnell was too fast for him. The lion even went on the offensive, swiping at the bovine’s snout whenever the bull came near. One blow opened a gash in Panthera’s nose and blood began pouring out. The wound was made worse when the bull scraped his snout against the ground in an attempt to get low enough to attack Parnell with his horns.

When Panthera charged again, Parnell leapt into the air and came down on the bull’s neck. The bull lacked the thick hide that had protected Ramadan, so Parnell’s teeth sunk deep, opening an artery. Blood poured down Panthera’s body. Although the bull managed to free himself by stepping on Parnell’s legs, it looked like the lion was about to take down an animal twice his size.

Instead of capitalizing on Panthera’s injuries, Parnell went to the edge of the cage and lowered himself against it. In one sense, the move was smart: the lion was situated so close to the bars, that Panthera feared rushing toward the animal from the side, lest he tangle his horns in the steel bars. If the bull attempted to hit Parnell directly, there was a good chance that he’d miss and hit his head on the side of the cage. No matter what Panthera did, Parnell would be in a good position to capitalize on his opponent’s mistake.

Unfortunately for Parnell, he didn’t consider that the bloodthirsty crowd would refuse to accept a temporary reprieve in action. When Panthera’s attempts to attack Parnell failed, and both animals stopped fighting, the spectators began hissing and booing. After minutes with no action, Boone or one of the venue’s owners decided to push the action. A vaquero reached through the cage and strung a noose around Parnell’s neck. The cowboy then threaded the rope to the other side of the cage and pulled, dragging the lion to the center of the cage. Parnell, lacking oxygen from the assault, and unable to move with the rope around his neck was defenseless.

Now that his opponent was safely away from the steel bars, Panthera backed up and charged. Because Parnell was unable to move, the bull did not have to readjust his aim, allowing all of his momentum to come down on the lion. The blow was devastating. The lion crumbled into a ball. Panthera didn’t give up, continuing to gore the downed Parnell. With one devastating blow, the bull drove a horn through the lion’s shoulder. Panthera then lifted his massive head with Parnell still dangling from his horn and marched proudly around the arena. Only after the jungle cat ceased moving did Boone call an end to the fight. He’d finally managed to euthanize his man killing lion.

The Mexican crowd cheered its champion. Panthera had defeated both of the animals put against him, making a considerable amount of money for those who’d bet on him. He was a temporary hero to the people of Mexico. It’s unclear what happened to the animal after his second battle. One report says that Panthera lost too much blood and died soon after the match. Another account holds that the animal survived his wounds. If so, it would not be hard to imagine Panthera living out the rest of his life as a breeding bull.

Boone was not happy. He couldn’t believe that Parnell had lost. He’d even reportedly bet a significant amount of money on the animal. Apparently, this financial loss offset the money he’d made in putting on the event. He’d be leaving Mexico poorer than he’d come.

Upon returning to the United States, Boone became depressed and even contemplated suicide because of his financial situation. One would like to believe that the depression was not all based on economics. Perhaps the lion tamer began to contemplate the gravity of what he’d done. He’d taken two majestic animals and thrown their life away for the entertainment of unappreciative, blood-thirsty audiences. After killing two men, Parnell needed to be euthanized, but should the animal have died amid a chorus of applause?

Boone continued to train animals after he returned from Mexico, and it seems that he recovered from his financial instability. He added a monkey; Holy Moses, a two-humped camel; and a “sociable pig” to his cadre of animals. He also introduced new acts to his circus, including Hootchie Cootchie, a bear who drank booze and Bob Fitzsimmons, a boxing kangaroo.

Boone still had trouble with his lions. Two of the animals killed another trainer and a lion escaped its cage while Boone was touring in Memphis.

By 1901, Boone had grown weary of the circus business, writing to a friend “I am tired of traveling and want something steady.” Soon thereafter, Boone sold his animals and retired to San Francisco, where he died in 1903.

The U.S.-Mexican border continued to host interspecies cage fights. In El Paso in 1902, a lion once again took on a bull, with the bull again emerging victorious in the encounter. Another fight saw an American buffalo taking on a bull. In this instance, the two animals rammed one another head on with the heavier buffalo managing to concuss the bull and win the fight. Even today, animals are forced to fight for the amusement of human in Mexican border towns.

E. Daniel Boone had put on a battle never before seen in world history. The show, however, did not have the effect that he intended it to. The audience who witnessed an American grizzly fight an African lion had no appreciation for what they were watching. Instead, they wanted blood and nothing more. Boone did not find money, fame, or gratitude from his animal fights. Only depression and loss of life.

Brad Folsom

COMING SOON TO HISTORYBANTER.com: Which president would win in a cage fight?