#1 – History Banter Podcast, episode 1: Lincoln (2012)

#1 – History Banter Podcast, episode 1: Lincoln (2012)

#2 – History Banter Podcast, episode 17: Gone with the Wind (1939) w/ Dr. Harland Hagler

#2 – History Banter Podcast, episode 17: Gone with the Wind (1939) w/ Dr. Harland Hagler

#3 – History Banter Podcast, episode 19: Boardwalk Empire (HBO) w/ Dr. Alexander Mendoza

#3 – History Banter Podcast, episode 19: Boardwalk Empire (HBO) w/ Dr. Alexander Mendoza

Top 3 most viewed History Banter originals

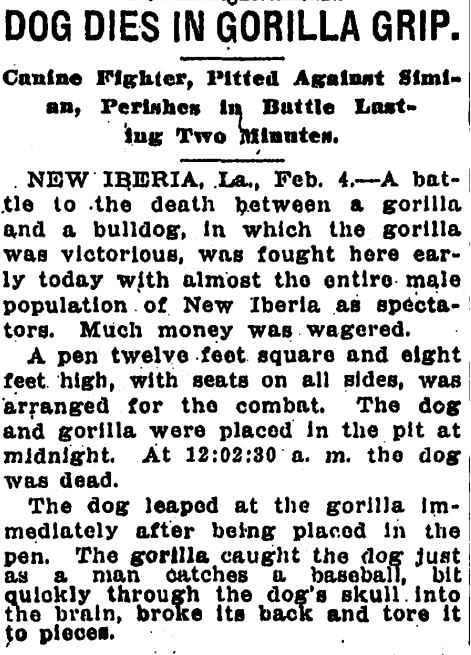

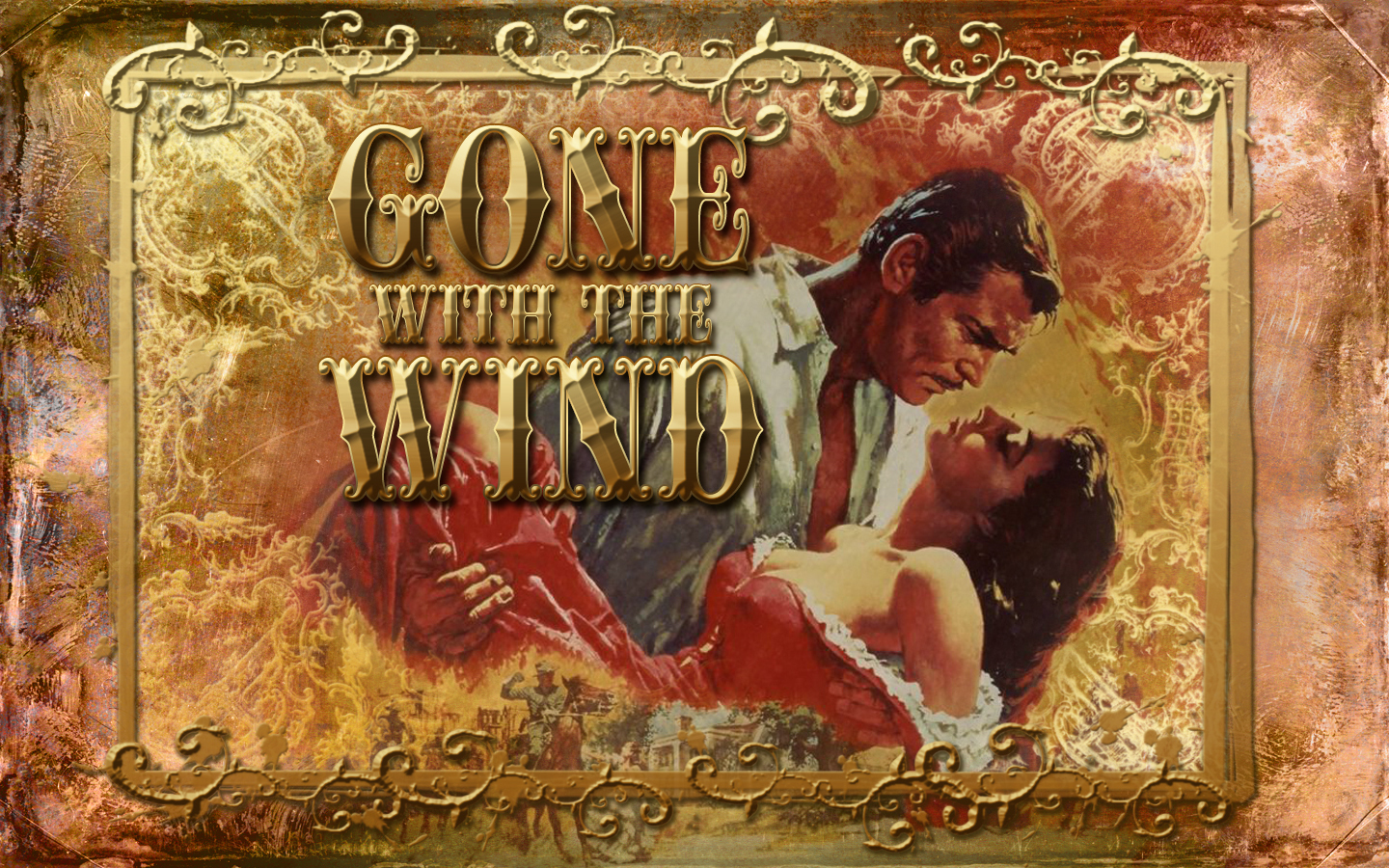

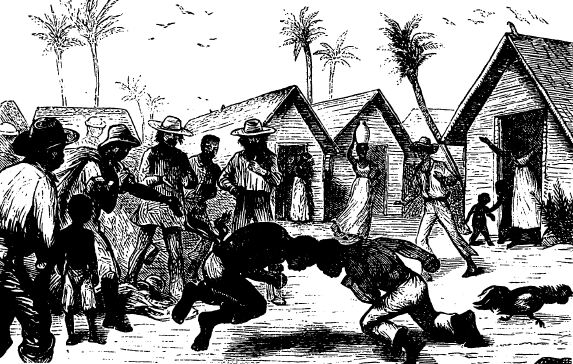

#1 – “Yes, Mandingo Fighting Really Happened” By Brad Folsom

#1 – “Yes, Mandingo Fighting Really Happened” By Brad Folsom

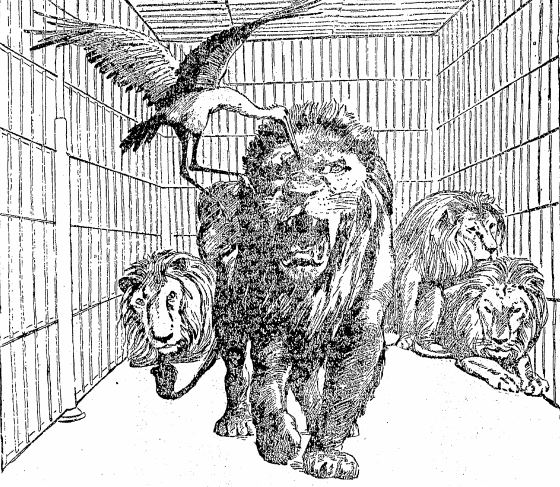

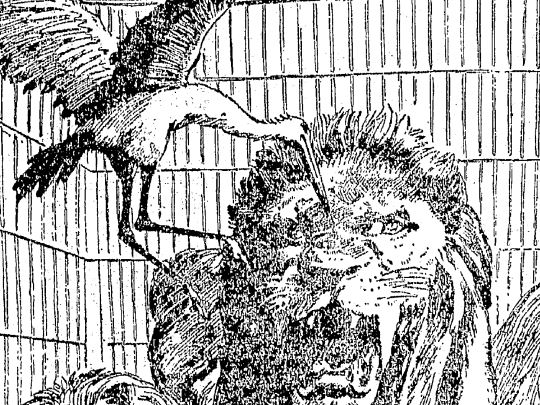

#2 – “When the Lion fought the Bear: Interspecies Cage Fighting on the Mexican Border” By Brad Folsom

#2 – “When the Lion fought the Bear: Interspecies Cage Fighting on the Mexican Border” By Brad Folsom

#3 – “The Ten Hottest, Most Badass Women of Stalingrad” By Brad Folsom

#3 – “The Ten Hottest, Most Badass Women of Stalingrad” By Brad Folsom

Top 3 most shared/retweeted Images of the Past

#1 – Baby cages, popular in the 1920s and 1930s as a space-saver for apartment-dwelling parents, and as a “safe” way to get fresh air and sunlight for your baby.

#1 – Baby cages, popular in the 1920s and 1930s as a space-saver for apartment-dwelling parents, and as a “safe” way to get fresh air and sunlight for your baby.

#2 – An ad from the 1940s, using Adolf Hitler to promote abstinence among American youths

#2 – An ad from the 1940s, using Adolf Hitler to promote abstinence among American youths

#3 – A french vampire-hunting kit, from the mid-19th century

#3 – A french vampire-hunting kit, from the mid-19th century

Top 3 coolest stories we read this year

#1 – “The Crazy, Ingenious Plan to Bring Hippopotamus Ranching to America,” from Wired Magazine

#1 – “The Crazy, Ingenious Plan to Bring Hippopotamus Ranching to America,” from Wired Magazine

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2013/12/hippopotamus-ranching/

#2 – “6 Mind-Blowing Things Recently Discovered From WWII,” from Cracked.com

#2 – “6 Mind-Blowing Things Recently Discovered From WWII,” from Cracked.com

http://www.cracked.com/article_20335_6-mind-blowing-things-recently-discovered-from-wwii.html

#3 – “For 40 Years, This Russian Family Was Cut Off From All Human Contact, Unaware of WWII,” from Smithsonianmag.com

#3 – “For 40 Years, This Russian Family Was Cut Off From All Human Contact, Unaware of WWII,” from Smithsonianmag.com

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/For-40-Years-This-Russian-Family-Was-Cut-Off-From-Human-Contact-Unaware-of-World-War-II-188843001.html

Not serpents in the sunshine hissing;

Not snake in tail that carries rattle;

What 's so startling about it? Nothing at first glance; it just seems like some nonsense about snakes. And it is, except for the fact that one of the snakes has a rattle on its tail, which means that the passage must be referring to a species of rattlesnake. Here 's why that 's interesting: rattlesnakes are native to the Americas, and were unknown in Europe, Africa, or Asia until after Christopher Columbus 's voyage to the New World in 1492. The Roman author, writing around 90 A.D., some 1,400 years before Columbus, shouldn 't have known about the animal. But according to this passage, he did. How 's this possible?

Let 's throw out natural explanations. There 's little chance the Romans were talking about a now-extinct or undiscovered species of Old World rattlesnake. There 's no fossil evidence of such an animal existing. It 's also unlikely that the Romans were talking about a known form of European or African snake. While plenty of Old World snakes twitch their tails, none produces a sound anything like a rattle (and Roman infants had rattles the same as ours today, so it 's not a matter of acoustics). It 's also improbable that a rattlesnake somehow survived a transoceanic voyage on a piece of driftwood, only for a Roman to find it, bring it back to health, and display it for the author in question. Therefore, if a rattlesnake made it to Rome alive, humans brought it.

This, then, implies contact between the Old World and the New before Christopher Columbus 's 1492 voyage. This, in turn, would mean that either American Indians brought a rattlesnake to the Old World, or Romans sailed to the Americas, picked up rattlesnake, and returned it across the Atlantic to Italy.

Neither idea is totally farfetched. We have evidence that at least one group of Europeans came to the New World and returned to the Old with souvenirs of their voyage. In approximately 1000 A.D., Vikings crossed the northern Atlantic and settled in Newfoundland, where they traded and fought with local Indians. After an undetermined amount of time, the Vikings abandoned Newfoundland and returned to the Old World, bringing some American Indians with them. Oral and written histories, archaeological evidence, and DNA studies confirm that this transatlantic crossing occurred at least once and possibly multiple times.

Other Pre-Columbian Old World-New World connections are on more shaky ground. Because there are pyramids in both Egypt and Central America, this has led some to conclude that Egyptians must have sailed to the New World and taught Central Americans how to build pyramids. Architectural historians and anyone with a basic knowledge of how shapes work counter that a wide variety of cultures constructed pyramids because it was the easiest shape to build using stone. If someone working in the days before steel I-beams wanted something big, it would have to be a pyramid. Try building a square structure the size of the pyramids without the roof caving in.

Another possible Africa-New World connection involves the Olmecs, who lived in Central America from 1500 to 500 B.C. According to fringe historians, Olmec statues depict sub-Saharan African phenotypical features, which would indicate that Africans must have been in Central America to serve as a model for these statues. In some ways, this theory makes sense. Sub-Saharan Africans traveled off the coast of Africa in large boats capable of holding over twenty people. It would not be unreasonable to assume that over the course of history, one of these boats became lost and sailed on ocean currents to the Americas (there are plenty of stories of people surviving long periods at sea in modern times).

The only problem with the Africa-Olmec correlation, then, is that the statues are the sum total of evidence for this connection. There 's no African DNA in Olmec descendants and archeologists haven 't uncovered African artifacts at Olmec sites. So the African-appearing statues may be evidence of Pre-Columbian crossing, or they could be an artist taking liberty with his subjects.

Some believe that there were voyages from the New World to the Old. Columbus, himself, mentions unusual looking people washing up on Ireland in 1477 A.D. Spanish author Bartolom de las Casas recounts a similar incident occurring in the Azores a few years later. Owing to ocean currents, these mysterious people could have been Inuits who 'd drifted off to sea in their canoes. Some historians even contend that the arrival of these unusual people inspired Columbus to believe a westward voyage was possible.

Although it may seem unfeasible for a technologically unsophisticated society to make such a long voyage, the Polynesians of the Pacific prove that it could have happened. At around the same time that Columbus was contemplating sailing west to reach China, there were Polynesians traveling over 3,000 miles from one Pacific Island to another. They may have even been the first Old World society to land in the American mainland and may have introduced Eurasian chickens to South America. Although this idea had yet to be proven, because Polynesians traveled extensive distances with animals 'they introduced pigs to Hawaii 'they support the possibility that a rattlesnake could have survived a trip from America to the Old World.

So Africans and Polynesians may have gone to the Americas before Columbus, and Indians may have gone the other way. What about non-Viking Europeans crossing the Atlantic? Rome, after all, is in Europe. Just like the others, there are plenty of stories saying that Europeans reached the New World before Columbus, but except for the Vikings, these accounts hold even less water than the Africa-Olmec connection. There 's the story of the Welsh explorer who sailed to the Americas in the 12th century and built fortresses in Kentucky and Alabama. There 's also the belief that Phoenicians or the lost tribe of Israel sailed to the New World and left stone inscriptions as evidence of their journey. Almost all of these inscriptions have turned out to be hoaxes. As are stone carvings saying that the Knights Templar made it to Minnesota, the Vikings to Oklahoma, and Hebrews to New Mexico.

Even if some of these European voyages took place, they were one way. Did anyone besides the Vikings travel across the Atlantic and make a return voyage? Again, all we have are vague stories. A 6th-century Irish monk claimed to have sailed west, found a mysterious land, and returned safely to Ireland, but the descriptions he left behind are vague and likely metaphorical. Writers in Mali say that 400 ships crossed the Atlantic in the 1300s. The only vessel to return from the trip bore tales of fighting with dark-skinned people, which some historians presume to be Indians. Again, this may be true, but evidence is scant. There 's also the claim that Chinese reached the New World in the 1400s. Although the Chinese did have an impressive navy at that time and theoretically could have sailed to the Americas and back, there 's zero evidence they did so. The historian who made up this claim is an idiot.

But what about the Romans? If any group of people other than the Vikings could have reached the New World and returned it would have been the Romans, even though they were in their heyday 1000 years before the Vikings. The Romans had an impressive navy, their ships frequently sailed off the coast of Spain and England, and archeologists have found evidence that they colonized the Canary Islands in the Atlantic. Although Roman vessels weren 't designed for crossing large distances of open ocean, it 's very possible that one became lost at sea and wound up in the New World. Because the Romans used Greek mathematician Herodotus 's estimation of the world 's size 'which was much more accurate than Columbus 's 'it 's possible that they could then have made a return voyage carrying exotic animals.

Except for my rattlesnake reference, however, there 's no written evidence that Romans made a Pre-Columbian Atlantic crossing. Popular histories often say that archeologists have uncovered Roman coins in Aztec or Mayan tombs, but I 've never seen a primary source to these claims. They seem to be based on unfounded rumors. There is, however, one intriguing archeological find that may indicate Roman-American Indian contact. In 1933, archeologists near Mexico City uncovered a terracotta head buried with Pre-Columbian Indian artifacts. Interestingly, the head bears European facial features and is in a similar art style to statues from ancient Rome. Although some regard the head as a hoax, many legitimate historians believe it may be evidence that Romans arrived in the New World. The consensus among supporters is that a Roman ship was blown off course and wrecked on the coast of Mexico.

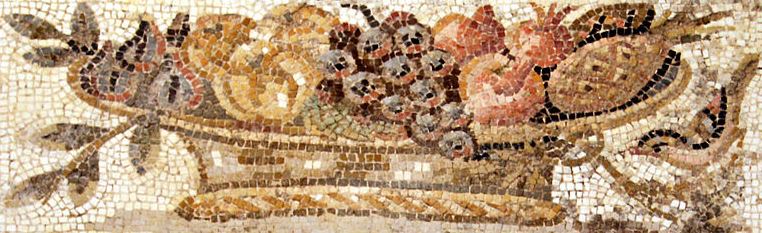

But again, getting back is a whole different story. Is there any evidence that Romans went to the America 's and returned? Sorta. A depiction of a fruit bowl on a mural in Pompeii and a mosaic hanging in the National Museum of Rome may be evidence of such a journey. Like my rattlesnake passage, at first glance, there 's nothing special about the mural and mosaic. They looks like something that would be seen in a twentieth-century art classroom. Just a bunch of fruit. On further inspection, however, one of the fruits shouldn 't be there: a pineapple. The grapes, figs, and apples are from Europe and were a staple of the Roman diet. The pineapple, on the other hand, is from the Americas. As far as we know, Columbus first brought a pineapple to the Old World in 1493.

Botanists and historians say the thing on the right is a pine cone. They’re probably right, but it sure looks like a pineapple. And why put a pine cone in with your fruit? It’s probably dirty.

So what 's the story with the pineapple in the mural? Botanists claim that it 's nothing more than a pinecone from a native Italian tree that bears a striking resemblance to the pineapple. The pineapple isn 't really a pineapple, but a pinecone. Romans included pinecones in their depictions of fruit because they were meant to represent virility. These critics are probably right. After all, how likely is it that a pineapple would survive an Atlantic journey in good enough shape to have its seeds planted and have the resulting tree survive long enough to bear fruit. That’s a stretch. But man, that thing looks like a pineapple.

Where does that leave my rattlesnake? Will it be the final piece of evidence that convinces historians that there was Pre-Columbian contact between the Old World and New? Will I be arguing with historians who seek to explain it away like the pineapple in the mural and the mosaic? Will I hear 'the Roman author was speaking about the noise the snake made with its mouth, the Romans tied bells to snakes, the author was speaking in metaphors and the snake was meant to represent childhood, ' or some other explanation? Will my snake go on the pile of possible, but unlikely evidence of Pre-Columbian travel?

Nope. It won 't even get that far. I fucked up. After thinking about it for awhile, I realized that I 'd just read a really shitty translation of the Roman text. The rattlesnake was just a snake. The author was translating to make the original text flow in English as it did in Latin, not for historical accuracy. He wanted it to sound like a poem. He was trying to rhyme and added the line 'not snake in tail that carries rattle ' to do so. He either didn 't know or didn 't care that there were no rattlesnakes in the Old World. A different translation of the same line says 'the viper scorched by the midday sun. ' Nothing about a rattle.

Here 's the rub: Pre-Columbian contact probably happened somewhere, sometime, whether it was the Romans, Egyptians, Phoenicians, or American Indians themselves. A boat became lost, drifted off, and sailed on ocean currents until reached the other side of the Atlantic. This probably happened at least once, but I don 't know if we should worry about it too much, because what likely followed was the wayward ocean goers either dying of disease or being killed by confused locals. If they survived, they probably adapted to the local culture and lived out their lives quietly. It 's doubtful that the newcomers reached high enough in their new society’s hierarchy to influence its development. And if someone, somehow did make it to the other side of the Atlantic and back, we 'd probably have more evidence than a vague reference to a rattlesnake in a poem.

Brad Folsom

A gunshot destroyed the idyllic scene and Fimbres watched as his wife slumped and fell from her saddle, somehow managing to shield her son before hitting the ground with a thud. Before Fimbres could come to his wife 's aid, Apache Indians poured from a hiding spot and began to attack the downed woman with knives. One Apache grabbed Fimbres 's young boy from his mother 's lifeless arms, mounted a horse, and rode away.[ii]

Seeing the scene unfold in front of him, Fimbres made a decision that he 'd regret for the rest of his life. He turned his horse and fled. Although he was armed, there was no way that he 'd be able to fight off what may have been dozens of Apaches by himself. If he tried, he 'd be throwing away not only his own life, but that of the daughter he carried with him. Taking one last look at the Apaches massacring his wife and kidnapping his son, Fimbres wheeled about and galloped towards the nearest ranch.[iii]

After hiding his daughter and recruiting help, Fimbres returned to the scene of the Apache attack. What he found would horrify him and change the course of his life forever. His wife had been chopped to pieces. An unborn child ripped from her womb. The Apaches and Fimbres 's son were long gone, the Indians having likely taken the boy to incorporate into their tribe. The sight of his wife 's mutilated body and the thought that the people who had killed her would be raising his son changed the normally peaceful Fimbres. From that day forward, he vowed to find his son and exact vengeance on the Indians who 'd killed his wife. He wanted to hunt the Apaches to extinction.[iv]

In some ways, Fimbres 's story resembles many others. Indians kidnapped thousands of woman and children throughout the history of northern Mexico and the American Southwest. In some instances, these kidnappings led surviving friends and family members to seek out their kin and exact retribution on the Indians who caused their loved ones harm.

The raid on Fort Parker and the kidnapping of Cynthia Ann Parker is perhaps the most famous of these incidents. In 1836, Comanche Indians raided the Parker family 's Texas home and raped, killed, and mutilated five persons they found inside. They absconded with five women and children, including nine-year-old Cynthia Ann and seventeen-year-old Rachel Plummer. From 1836 to 1845, James Parker, Rachel 's father and Cynthia Ann 's uncle, rode across the plains of Texas, seeking to rescue his kin and punish the Comanches who 'd killed his five family members. Almost losing his life of multiple occasions, James reclaimed his daughter, but never found Cynthia Ann (she would remain a member of the Comanches for most of her life, and would give birth to future Comanche Chief Quanah Parker). James Parker 's tireless quest would go on to inspire what many consider the best western film of all time, John Wayne 's The Searchers.

In many ways, Fimbres 's journey to find his son resembles The Searchers, but one thing sets it apart: Apaches attacked the Fimbres family on October 26, 1926, over 90 years after Cynthia Ann 's kidnapping and 40 years after the last major Indian attack in the United States. Whereas every other Indian tribe on the North American continent had died, moved on to a reservation, or amalgamated into European culture, the Apaches who had attacked Fimbres had held out in the mountains of Mexico well into the 20th century and continued to live as they had for the last 300 years. A world with trans-Atlantic flight, rockets, and Hitler, was home to unconquered Apaches.

The Apaches were a semi-nomadic tribe who in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries used European-introduced horses to conquer vast swaths of territory in what is today Texas, New Mexico, and northern Mexico. Although the Apaches settled down for short periods and grew some of their own food, they spent much of their lives raiding neighboring tribes and European settlements for goods and livestock. Although the Apaches usually mutilated and killed adult males they encountered in these raids, they took women and children back to their camps to adopt into their tribes.

These practices earned the Apaches numerous enemies. The Comanche Indians hated the Apaches. So did the Spanish, who, after failing to subdue the Apaches in the 17th and 18th centuries, began a war of extermination on the Indian tribe. When Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, it continued its mother country 's attempts at genocide by paying scalp hunters for Apache scalps. The Apaches survived these efforts, and it was not until the United States Army moved on to the Southern Plains in the late 19th century with automatic-firearms that most Apaches finally gave up raiding and retired to government-run reservations.[v]

One Apache Chief, Geronimo, held out in spite of the U.S. Army 's efforts. Leading a band of 38 men, women, and children, Geronimo raided in the United States throughout the 1880s, and evaded retaliation by crossing into Mexico to hide in the nearly impenetrable Sierra Madre Mountains. It took the American and Mexican armies working together, with each devoting thousands of soldiers, to track down and finally arrest Geronimo in 1886.

For a long time, most outside Sonora thought that Geronimo 's capture marked an end to the Indians Wars; that the only surviving Apaches lived on reservations. As Francisco Fimbres would come to find out, this wasn 't true. From 1880 to 1930, a tiny band of Apaches 'some fifty or so 'hid out in the Sierra Madres in Sonora, living in constant fear of being discovered. Apache mothers taught their children to walk softly and speak rarely. Lookouts held watch all hours of the day to warn of approaching trespassers.

Most of these surviving Apaches were women and children, as Apache males frequently died in the few instances they dared to raid outside of their mountain home. This made male children a commodity among Apaches, which, in turn, meant that given the opportunity, Apaches would kidnap Mexican boys to adopt into their tribe. Boys like Francisco Fimbres 's two-year-old son, Heraldo.

Before the day he lost his son and wife in 1926, Francisco Fimbres had lived a fortunate life. He was born into a wealthy ranching family with considerable influence on both the Mexican and American side of the border. In part, this owed to Fimbres 's father, a tough man who 'd earned respect fighting Indians in his younger days. Although Fimbres never fought Indians in his youth, he 'd likely been exposed to violence growing up. His town Nacori Chico was distant from government authority, meaning that bandits were a constant nuisance. And Fimbres, like most in Mexico, likely lost family members in the 1910-1920 Mexican Revolution 'a civil war that claimed the lives of almost one million people.

In spite of the chaos, it seems that the Fimbres family profited and grew their ranching empire, and when Fimbres 's father passed, he left his ranches and livestock to his son. Fimbres fortune increased when he married into his wife 's well-to-do family. By all accounts, the couple was in love, and they soon consummated their relationship by having two children. They were expecting a third when the Apaches attacked on October 26, 1926.

Most sources relay the version of events mentioned previously. Fimbres and his family were on their way home when a group of Apaches emerged from a hiding spot, shot Fimbres 's wife, and grabbed his son. Unwilling to endanger his daughter in what would likely be a suicidal rescue effort, Fimbres fled, hid his daughter, and returned to the scene with friends. At that point, Fimbres found that the Apaches had mutilated his wife and taken his son.

While this version of events is the most commonly cited, other sources vary on details 'the Fimbreses were camping, the Apaches attacked them at their home, etc '. In some versions of the story, Fimbres looks heroic. He tried to shoot the Apaches, but his gun jammed and the Apaches attacked him, stabbed him, and tried to drag him from his horse. Bleeding and unarmed, Fimbres protected his daughter and barely managed to escape. Other accounts paint Fimbres in a less flattering light: there were only a few Apaches, they were all female, and none had firearms. Instead of shooting Fimbres 's wife, these Apache women emerged from hiding, pulled her from her horse, and sliced her to pieces while Fimbres watched in horror. In this version of the story, Fimbres had a loaded six-shooter, but chose to flee the scene anyway.

It 's unclear which of the many accounts is most accurate, but one thing is certain: Fimbres 's life changed that day. Upon returning to the scene and finding his son missing and his wife torn to shreds by Apache knives, Fimbres decided to 'rescue his son and avenge his wife or die trying. ' From then on, he would always wear a black armband and black hat and he became obsessed with vengeance. He wanted to kill every Apache that remained in the Sierra Madres and he would set out into the mountains on ten different occasions to do so.[vi]

Fimbres made his first trek into the Sierra Madres in the winter of 1926. In preparation, he traveled to Douglas, Arizona where he consulted with a woman named Lupe who made her home on one of Fimbres 's ranches. As a child, Lupe had lived with the Sierra Madre Apaches, so she knew the group better than any other. When Fimbres asked if his son were still alive, Lupe replied in the affirmative, but she warned that locating him would be difficult. The Apaches knew how to cover their tracks and were always quiet, moving like ghosts from one camp to another. Lupe recalled the horror she felt as a child when an older Apache woman strangled one of her friends to death for being too loud. When Fimbres asked if Lupe would join him in the Sierra Madres, the woman shuddered. She feared that if caught, the Apaches would regard her as a traitor and torture her. Fimbres would have to find someone else. Before he could depart, Lupe begged Fimbres to hold off his search, at least for a while. She warned the vengeance-obsessed father that if he went after his boy right away, the Apaches would throw the child off a cliff to stop his pursuit. If instead, Fimbres waited a few months or years, the Apaches would develop an affinity for the boy and would be less likely to harm him.[vii]

Unable to fathom the idea of allowing the Apaches to pollute his son 's mind any longer, Fimbres ignored Lupe 's advice, gathered friends and family as volunteers, and set out for the heart of the Sierra Madres in November 1926. Although there is no record of this first expedition, it must have been perilous owning to the harsh nature of the environment. One resident noted that 'there is probably no other place as rugged and naturally secluded on the entire North American continent than where these Apaches live and from where they have challenged the world this last half century. ' Dense deciduous forests, craggy rocks, sheer cliffs, and caves cover the Sierra Madres, making the region 'so rugged that a wildcat can hardly get around there. ' Because Fimbres set out in November, he 'd also have to deal with the region 's notoriously heavy snowfalls.[viii]

Fimbres and his cohorts traipsed the Sierra Madres for weeks without seeing another human, their only companions bears, cougars, and other Sierra Madre wildlife. Massive pines and sheer cliffs dominated their view. Occasionally, the party would have come across abandoned stone castles and fortresses, remnants of long gone Indian civilizations that had been driven from the Sierra Madres by drought, disease, and Apaches. By the 1920s, the stone buildings ' only inhabitants were ghosts.

After weeks with no sign of the Apaches or his son, Fimbres returned to civilization, resupplied, and resumed his search in a different area of the Sierra Madres. A second trip yielded no sign of his son. Nor a third. With each trip, his entourage grew smaller, but Fimbres kept up the search, venturing into the Sierra Madres on some ten different occasions from 1927 to 1928. Each time he emerged from the wilderness no closer to finding the Apaches or his son.

In 1928, just as it must have seemed like he 'd spend the rest of his life in fruitless pursuit, fortune struck. While resupplying in a small Sonoran town, Fimbres ran into Gilberto Valenzuela, a former Secretary of the Interior who was currently running for President of Mexico. Valenzuela listened to Fimbres 's story and decided to help, putting him in contact with local officials. They informed the press about the missing boy and helped Fimbres recruit eleven experienced trackers for his next expedition. These men included Moroni Finn, an oversized Mormon miner whose family had moved to the Sierra Madres to escape U.S. anti-polygamy laws; Cayetano Huesca, a professional trapper; and Ramon Quejada, a well-traveled and well-liked man who 'd spent his life on the U.S.-Mexico border.[ix]

The twelve men set off into the Sierra Madre wilderness in the winter of 1928. They traveled on foot to avoid alerting the Apaches with the sound of approaching hoofs. The men also camouflaged themselves in straw hats and rarely lit a fire to avoid detection, a measure that proved difficult because the winter of 1928-1929 was especially harsh. At one point, perhaps owing to the difficulty of travel and lack of heat, Ramon Quejada fell ill and almost succumbed to fever. Thankfully, the expedition ran across a Chinese vegetable farmer willing to return the sick man to civilization. Fortune favored the remaining men early in 1929 when they came across a series of still smoldering Apache campfires. Unfortunately, with supplies running low, it was necessary for the men to return to civilization, but at least they now had a rough guess at where the Apaches ' lived.[x]

The next fall, Fimbres, Maroni Finn, and the volunteers set out again and this time, they located the Indians ' winter camp. Fimbres snuck so close to it, in fact, that he swore he could see his son among the Apaches. Unfortunately, the camp was atop a steep cliff and surrounded by 'a natural fortress. ' If the men tried to attack, they 'd suffer heavy casualties. So Fimbres made a decision. He 'd return to civilization, recruit a well-armed army, and overrun the Apaches.

Fimbres and the remaining members of the expedition descended the Sierra Madres and informed newspapers that they were looking for volunteers. The date of the departure would be May 7, 1930. Fimbres then requested permission from the Mexican government to bring members of the Sonoran militia on the expedition, as well as volunteers from the United States. Now that Fimbres knew where the Apaches were, he wanted to make sure that none escaped. He 'd take as many well-armed men as he could.[xi]

The plan fell apart. Although the Mexican and American governments offered tacit approval at first, they soon rescinded it. In the United States, so many volunteers lined up, that recruiters started charging for the expedition. Soon rescuing Fimbres 's son became an afterthought, with one organizer bluntly asking, 'Why not join us and get the best vacation you ever had, a delightful experience, a fine comradeship, and see some of the most wonderful country God ever made Noticing that its citizens were selling tickets to what amounted to a human hunt, the State Department forbid anyone to cross into Mexico to assist Fimbres. The Mexican government, for its part, initially offered soldiers, but it grew weary of the plan when it was revealed that many U.S. volunteers were mineral speculators looking to scout the Sierra Madres for mines. The idea of a private U.S. army on Mexican soil wasn 't pleasant either. So the Mexican government forbid Americans from joining Fimbres. It also rescinded its offer of militiamen. Fimbres could still kill Apaches without punishment and the government would provide firearms, but he 'd have to find his own men. Instead of an army the rancher recruited his uncle Cayetano Fimbres, some members of his previous expeditions, and a few Americans who violated their country 's orders and crossed the border. It would be Fimbres and twelve men. Twelve well armed men.[xii]

Interestingly, just as Fimbres prepared to depart, newspapers reported an interesting twist to the story of his child 's kidnapping: the Apaches may have specifically targeted Fimbres. When Fimbres was a child, his father was among a group of ranchers who 'd set off in pursuit of a group of Sierra Madre Apaches that had stolen some cattle. Although most of the thieves escaped, Fimbres 's father managed to capture their lookout, a twelve-year-old girl. The elder Fimbres took the child back to his ranch, prevented her from returning to the Apaches, and raised her into adulthood as a Mexican. The child grew up to be Lupe, the woman who 'd helped Fimbres before his first expedition. Lupe believed that her Apache mother had ordered the 1926 attack and kidnapping as revenge for Fimbres 's father taking her as a child. Her mother had been the one to kill Fimbres 's wife. In essence, the Apaches had attacked Fimbres as revenge for his father 's actions.[xiii]

If Fimbres recognized the irony of the situation, he didn 't show it. In April 1930, he and his twelve recruits headed into the Sierra Madres. Though they 'd prepared to stay in the field for months and had armed themselves to take on the Apache camp, their journey would be short. Not long after heading into the mountains, word reached the group that Apaches had attacked a nearby pack train. Abandoning any pretext of stealth, the men rode at full gallop toward the sight of the attack, where they noticed smoke rising from a distant campfire. It was the Apaches.

Fimbres and his entourage crested a ridge and spotted two Apache women and the known Apache leader, Apache Juan. The men managed to avoid detection until one of the Apache women noticed their arrival and shouted 'Nayak ! ' the Apache word for Mexican. Before she could utter another word, one of Fimbres 's crew fired a bullet through her arm, nearly separating it from her body. A second bullet ended the woman 's life. The remaining Apache female reached her rifle and leveled it at the oncoming men, but when she pulled the trigger, the gun jammed. She frantically tried to clear the barrel with her knife, but before she could do so, Fimbres 's men shot her dead.

Apache Juan managed to escape the initial barrage long enough to seek shelter behind a rock, and for two hours he exchanged gunfire with Fimbres and his crew. The Apache finally met his end when Cayetano Fimbres flanked him and shot him. Cayetano put a bullet in the Indian at point blank range to ensure that he was dead.

Fimbres and his group searched the surrounding countryside for Heraldo and the remaining Apaches, but found nothing. They then returned to the scene of the gunfight and scalped the two Apache women. Fimbres strung their flea-infested hair on his belt. He also decapitated Apache Juan, and took his head as a souvenir. The group left what remained of the three bodies to rot in the sun. Fimbres had not yet found his son, but he 'd finally drawn blood.

The men returned to civilization with the tokens of their victory. Fimbres placed the decapitated head of Apache Juan atop a stake in Nacori Chico and posed for a photo in the town square. The photo shows Fimbres holding the scalps, his crew standing menacingly in the background. A child, around the same age that Heraldo would be at the time, stands to left of Fimbres, looking excitedly into the camera, delighted to be included in the photo.

Newspapers in the United States and Mexico reprinted the photograph and reported on Fimbres’s successful hunt. For his part, Fimbres showed the Apache scalps to anyone who would look. One man who saw one of the gruesome trophies as a child and later recalled only that the memento 'was full of fleas. ' When someone asked if he had achieved his goal by killing the three Apaches, Fimbres shook his head and said that he still had work to do. He had to rescue his son.

He wouldn 't. Shortly after Fimbres returned to civilization, the remaining Sierra Madre Apaches discovered the bodies of Apache Juan and the two women. Heraldo was with them. What happened next was brutal. Seeking either to stop his father 's relentless pursuit or to avenge their dead kin, the Apaches strung the almost-seven-year-old Heraldo up to a tree and began stoning him. The boy, having lived with the Apaches for three years at this point, likely begged his new family to stop, but they didn 't listen. They kept throwing stones. At some point, it seems the Apaches cut the still-living child down from his perch and began carving him with a knife, nearly beheading him. With the child still breathing, the Apaches then threw him into an empty grave and covered it with stones, leaving the boy 's legs sticking out for the world to see. The Apaches then gave Apache Juan and their two women a proper burial and departed the scene.

A few days later, two Mexican travelers were overcome with the scent of rotting flesh and when they went to investigate, they found Heraldo 's grave. They dug the boy up and found him covered head to toe in traditional Apache clothing. Soon thereafter the men located Fimbres and relayed what they 'd found.

Fimbres was devastated. Some sources say that he realized he 'd made a mistake and questioned his decision to attack the Apaches without first making sure they had Heraldo. That maybe he should have waited longer for the Apaches to grow more attached to Heraldo, as Lupe had warned. Some say that Fimbres grew depressed, reclusive. Others say that his son 's death drove him further toward the path of vengeance. That he lost all sense of his humanity. That more than ever he wanted to eradicate the Apaches from the earth.

Fimbres may have achieved this goal. Following the news of Heraldo 's death, hysteria gripped Mexico and the United States. Newspapers exaggerated the threat the Apache posed by inflating their numbers from, at most, a few dozen to hundreds. Instead of stealthy thieves, the Apaches became heartless savages. Not only that, but newspapers falsely reported that Geronimo 's grandson, Geronimo III had taken over the Sierra Madre band and was preparing for all out war on Mexico.[xiv]

There would be a war, but most of the casualties would be Apaches. Instead of turning the other way when Apaches stole their cattle, as they 'd done before, Mexican men fought back, and from 1930 to 1935, what could be described as the last Indian war took place in Sonora. In 1932, a rancher chased a group of Apaches who 'd stolen some of his horses for twenty-five days. When he finally caught up to them, he put a bullet through a mother carrying her child, killed a second female, and forced a third to drop her child in order to escape. The rancher also shot an Apache male at the scene. Although he managed to escape, the rancher believed he later died of his wounds. Another group of ranchers came upon the woman who 'd abandoned her child, killed her, and hung her from a tree. The two Apache children survived the encounter, but when a Mexican family tried to raise them as their own, their stomachs couldn 't adapt to the change in diet, so they whittled away and eventually died of starvation.[xv]

It seems that the remaining Apaches sought vengeance. Instead of retreating deeper into the Sierra Madres, in 1933, the few Apache warriors raided Fimbres 's hometown and killed and scalped three ranch hands. In response, John Chavez, whom American newspapers called a 'Mexican Paul Revere, ' laid a trap for the Apaches and killed five of their number. In a separate occasion, Fimbres 's old Mormon acquaintance, Moroni Finn, killed another five Apaches. One person captured an Apache child. Another shot a fleeing woman. The killings added up, and by 1935, the Apache attacks stopped. The Sierra Madres grew quiet. The last Indian war was over, with the same result as those that had come before. The Indians lost.[xvi]

In 1937, an anthropologist named Helge Ingstad recruited Apaches from the Fort Apache Indian reservation in Arizona and asked them to accompany him into the Sierra Madres. He wanted to find what remained of their Sierra Madre kin. For three months, Ingstad and the Apaches scoured the countryside, finding long abandoned campsites, but no Apaches. Occasionally, the reservation Indians would yell out to let their brethren know that they were friends and only wanted to talk. The only response was echoes. More than once, Ingstad swore that he saw Indians watching him from behind trees, but each investigation revealed that no one had been there. Only the ghosts of the Sierra Madre Apaches remained.

Brad Folsom

[i] Helge Ingstad, The Apache Indians: In Search of the Missing Tribe (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 126. This is just one version of Fimbres’s story. Newspapers and oral histories recount numerous others. See also Grenville Goodwin, The Apache Diaries: A Father-Son Journey (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

[ii] Ingstad, The Apache Indians, 126.

[iii] Ingstad, The Apache Indians, 126.

[iv] Ingstad, The Apache Indians, 126.

[v] See Mark Santiago, The Jar of Severed Hands: Spanish Deportation of Apache Prisoners of War, 1770-1810 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011) for more of the brutal treatment of the Apaches by the Spanish. This is one work among many on the subject.

[vi] 'Francisco Fimbres Se Ha Vengado, ' Hispano-America, February 21, 1931.

[vii] Ingstad, The Apache Indians, 126-127.

[viii] Ingstad, The Apache Indians, 85, 127.

[ix] Ingstad, The Apache Indians, 127.

[x] Ingstad, The Apache Indians, 127; 'Fears Felt for Party Seeking Indian Raiders, ' Tampa Morning Tribune January 14, 1929.

[xi] 'Attack on Indians Planned in Arizona, ' Riverside Daily Press, November 27, 1929.

[xii] 'Attack on Indians Planned in Arizona, ' Riverside Daily Press, November 27, 1929. 'Into the Wilds to Rescue a Baby, ' San Diego Union, April 27, 1930; 'Officials Scent Publicity Stunt in 'Expedition, The Rockford Register-Gazette, April 25, 1930; 'Here 's A Chance to be Indian Fighter, ' The Alto Herald, April 10, 1930. Some sources put the volunteer army as high as 1,000 men. 'Father Returns with 3 Scalps, ' Riverside Daily, February 2, 1931.

[xiii] 'Into the Wilds to Rescue a Baby, ' San Diego Union, April 27, 1930.

[xiv] 'Apache Warcry Rings Again, ' Springfield Union, October 21, 1934.

[xv] Goodwin, Apache Diaries, 110-111.

[xvi] 'Indians Scalp 3, ' The San Diego Union, April 23, 1933.; 'Ranchers Slay 5 Apache Braves in Sonora Fight, ' The San Diego Union, March 7, 1930; 'Apache Warcry Rings Again, ' Springfield Union, October 21, 1934.

Richard Lawrence gripped the two single shot pistols concealed in his jacket as he waited for the president to emerge from the Capitol Hill rotunda. Although he was planning to kill one of the most powerful men in the world, Lawrence was calm. As he saw it, the president deserved to die. Not only was he tyrant, but he 'd killed Lawrence 's father and stolen Lawrence 's inheritance. Sure, some people would be upset about the shooting, but Lawrence didn 't care. Everyone was below him. He was the King of England.

January 30, 1835 was a particularly cold, damp day for Washington D.C., and Andrew Jackson ached as he stepped into the open air. After a lifetime of fighting on the battlefield and off, the president 's body 'still carrying two bullets as tokens of a hard-lived past 'didn 't move like it used to. Humiliatingly, the man who earned the nickname 'Old Hickory ' for his strength and perseverance in the War of 1812 had to lean on his Secretary of Treasury just to walk a few feet.

Although his body was weak, Jackson mind remained sharp. Scanning the crowd outside of the capitol building, the president 's eyes locked on a short, mustachioed man with his hands in his jacket and a smirk on his face. When the man noticed Jackson staring in his direction, he averted his gaze. His smirk vanished. Jackson remained wary of the man, but didn 't regard him as a threat. The old soldier had enemies, but he felt they were too cowardly to attack him in person. They 'd rather snipe at him behind his back. Besides, Jackson thought, no one had ever tried to assassinate the sitting President of the United States.

Moments later, this would no longer be true. As Jackson approached the carriage that would take him back to the White House, he saw the mustachioed man taking something out of his pocket and walking in his direction.

Lawrence realized this would be his only chance for vengeance. When he came within eight feet of Jackson, he withdrew one of his pistols, aimed at the president 's chest, and fired. Smoke and noise filled the air. Jackson 's eyes grew wide.

What led Richard Lawrence to Capitol Hill that day? Why did he fire a gun at the President of the United States when he 'd likely be jailed or killed for doing so? What motivated America’s first presidential assassin?

The easy answer to these questions is insanity. Lawrence was insane. He was in a state of deep psychosis at the time of the shooting and likely suffered from paranoid schizophrenia. He 'd spent the past two years hearing and seeing people that weren 't there and had adopted a false persona. Instead of accepting a reality in which he was a moderately successful house painter, Lawrence had come to believe that he was the King of England and that President Jackson was the source of all of his problems.

Unfortunately, insanity alone can 't explain why Lawrence fired a gun at Jackson that day. If it could, then everyone with paranoid schizophrenia would try to kill the president. In reality, most people who are genetically predisposed to schizophrenia do not develop the disorder and those who do rarely try to murder another human being.

So why, then, did Lawrence develop this particular brand of violent, president-killing schizophrenia? Although the subject is still a matter of debate, recent research indicates that environmental and social factors can trigger the onset of schizophrenia and can alter the way the disease manifests itself in the inflicted. Lawrence 's particular set of life experiences, therefore, may have created an assassin.

Although Jackson didn 't intentionally provoke his assassin, he was responsible for creating one of the most hostile political atmospheres in American history, which may have led Lawrence to conclude that violence was an acceptable means of redressing grievances. Owing to his upbringing and military career, Jackson treated those who disagreed with him as enemies, an attitude he brought to the presidency. He saw members of the opposition party as traitors, threatened harm whenever he didn 't get his way, and used his office to punish those who’d wronged him.

As a logical reaction to the president 's attacks, political opponents demonized Jackson. They called him a tyrant and blamed him for the nation 's ills. Lawrence 's deranged mind accepted these portrayals as fact, and he grew to believe that he 'd be a hero for killing this man who 'd made everyone 's life miserable. One historian referred to Jackson as 'an obvious target for the demented in society. '

Here 's a look at the lives of the first presidential assassin and the man he hoped to kill.

People made fun of him

Like all who eventually succumb to paranoid schizophrenia, Richard Lawrence showed no symptoms of mental disorder in his early life. Born in England at the turn of the 19th century to a poor, nondescript family, Lawrence had little parental guidance growing up. His mother was not around during his childhood, his sisters were too young to provide maternal care, and his aunt went insane, became homeless, and died on the streets when Lawrence was a child. While Lawrence 's father was around for his son 's early life, he suffered from mental illness and would often sit alone, staring at a featureless wall for hours on end. It seems that this mental disorder affected his employment status. Lawrence remembered his father pushing a coal cart as a job, but the work wasn 't steady, he was often unemployed, and his family lived in poverty.

Perhaps hoping for a fresh start and better opportunities, in 1812, the elder Lawrence moved his family from England to Washington D.C., the recently constructed capital of the United States. The Lawrences arrived in their new home to find that their new country had just declared war on their old country–the War of 1812 would overshadow life in the U.S. capital for the next three years. Because of this, anti-British sentiment was high in D.C. Americans called recently arrived English immigrants 'traitors ' and politicians on nearby Capitol Hill debated whether or not to forcefully repatriate new arrivals like the Lawrences. In the midst of these deliberations, a British army invaded Washington D.C. and burned much of the city to the ground. This left British families like the Lawrences at the mercy of angry, vengeful D.C. residents. Lawrence gives no clue to the trouble he faced as a child except to say, 'people made fun of him. '

Life had already set Lawrence on a track to mental illness. Recent studies indicate that schizophrenia is more likely to manifests itself in persons who 1) were born into families with mental disorders 2) grew up in poverty 3) moved at a young, impressionable ages, 4) experienced discrimination in childhood, and 5) lived in urban areas. All of these things applied to Richard Lawrence. His father and aunt were mentally ill, he was raised poor, and he moved to a city full of people that hated him because of his nationality. It 's impossible to say that Lawrence would inevitably go insane, but it would be difficult to create a better cocktail of early life mental disorder determinants.

Old Hickory

The same war that set Lawrence on a path to insanity brought his future target, Andrew Jackson, to national prominence. Born along the North Carolina-South Carolina border on March 15, 1767, Jackson was thirty-three years the elder of Lawrence. In spite of their age difference, the two men had similar childhoods. Jackson was born to poor immigrant parents, he lost his mother at a young age, and he moved early in life. And like Lawrence, Jackson was thrown into a war in adolescence. During the American Revolution, British soldiers captured thirteen-year-old Jackson as he was delivering letters between patriot forces. When a British officer demanded that Jackson clean his boots, the teenager refused to do so. The officer punished this impudence by slashing Jackson across the face with a cutlass.

Whereas Lawrence grew introverted in response to early-life torment, Jackson became indignant and came to regard anyone who disagreed with him as an enemy. This attitude led Jackson to challenge multiple men to duels. One time, rivals shot Jackson in a bar.

Like Lawrence, Jackson moved early in life, relocating from North Carolina to Tennessee, where he became a lawyer and served Tennessee in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. In 1803, he bought a farm and staffed it with African slaves. Jackson, however, would make his name as a soldier, beginning his military career as a member of the Tennessee militia. When the War of 1812 broke out, Jackson led the Tennessee militia in subduing the British-aligned Red Stick Creeks in Alabama. During the campaign, Jackson displayed little sympathy for his Indian enemies or his men. He demanded complete obedience. His hard nature earned him the name 'Old Hickory. '

Although his actions against the Creeks earned praise, Jackson cemented his legacy as one of America 's most famous generals in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. Charged with defending New Orleans against 7,500 highly trained British soldiers, Jackson recruited Indians, pirates, freed people of color, and anyone else capable of shooting a gun into his army. When British forces marched on these rag tag defenders, Jackson ordered his men to fire cannons full of bits of metal into their lines. The attack was devastating, causing heavy casualties, and forcing the British to retreat. Newspapers throughout the United States carried news of the victory, launching Jackson to national prominence.

Jackson remained in the army following the end of the War of 1812 and he continued his no nonsense approach to discipline in spite of an end to hostilities. In one instance, he executed six militiamen who 'd mistakenly left the army when they believed that their enlistment was over. In 1816, Jackson 's forces invaded Spanish Florida to destroy a settlement of escaped slaves, and two years later, Jackson led his men into Florida, took over a Spanish city, and executed Englishmen he believed to be spies. Jackson 's brash actions displeased stodgy politicians in Washington, but the American public loved Old Hickory.

A Young Man of Excellent Habits

It would have been impossible to avoid news of Jackson 's exploits in Washington D.C., where Lawrence continued to live with his family until his father 's death in 1821. That year, Lawrence moved out and became an apprentice to one Mr. Clark, with whom he lived for three years while learning to paint houses and boats. It seems that Lawrence had a gift for at his new profession, with Clark noting that his apprentice 'was a young man of excellent habits, sober, and industrious. '

After completing his apprenticeship to Clark in 1824, Lawrence opened his own painter 's shop just outside Washington D.C. Owing to his training and impeccable work ethic, the business flourished and by 1828, Lawrence was one of the most sought after painters in the capital. Numerous congressional representatives even hired Lawrence to paint their homes, with one remarking that the young painter was an 'excellent workman ' whose conduct was 'correct and orderly. ' This reputation even earned Lawrence a job painting the White House, but no details of the visit survive.

Although Lawrence 's infectious personality, polite demeanor, and impeccable work ethic made him popular in D.C., the young man had few people that he could call a 'friend. ' He rarely went out on social occasions 'he seldom drank and never gambled. He sometimes studied the Bible, but Lawrence didn 't consider himself religious and rarely went to church. It seems, then, that for most of his youth, Lawrence 's only companions were his sisters, who described their brother as 'affectionate ' and 'kind. '

At some point in the early 1830s, Lawrence found a young woman that he felt that he could be himself around, and he began to court her. Details of their relationship are lacking, but it 's easy to see how the woman would develop an interest in Lawrence. He was young, intelligent, and, at a young age, already ran a successful business. It didn 't hurt that he was also handsome, possessing piercing dark eyes and jet black hair. Although short, the young painter dressed well, and he commanded attention whenever he entered a room.

It 's unclear if the woman ever viewed the young painter as more than a friend, but, for his part, Lawrence was in love and even told his sisters that he planned to marry the woman. In preparation, he worked overtime, saved up $800 dollars, and bought an empty lot in the city. He told the woman that he planned to build her a home on the lot and asked for her hand in marriage. She declined. The news broke Lawrence 's heart, and he fell into a deep depression. He started frequenting a salon across from the empty lot and would stand for hours on end, staring across the street, imaging what could have been.

Jackson

Like Lawrence, heartbreak would define Andrew Jackson. As a young man, Jackson fell in love Rachel Donelson Robards, and in 1790, he asked for the woman 's hand in marriage. Rachel wanted to marry Jackson, but she was already betrothed to an abusive husband. In order for the couple to wed, then, Rachel petitioned the Tennessee government for a divorce. According to the newlyweds, they waited for the state to grant the petition before marrying and moving in together. Unfortunately, it seems that in reality, Rachel and Jackson actually married before Tennessee granted the divorce. This would come back to haunt the couple when Jackson decided to run for President of the United States in 1824.

That year, Jackson ran as a member of the Republican Party against fellow Republicans John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. Owing to his famous reputation, Jackson easily won the popular vote, but he failed to gain a majority of electoral votes. This left the House of Representatives to decide who would be president. The House chose Adams after Clay dropped out of the race and told his supporters to vote for Adams over Jackson. When Adams then repaid Clay by making him his Secretary of State, Jackson grew incensed, claiming the two had made a 'corrupt bargain. ' Old Hickory then quit the Republican Party, formed the Democratic Party, and spent the next four years denouncing Clay and Adams. In 1828, Jackson once again ran against Adams for the presidency.

The 1828 election was one of the nastiest, dirtiest elections in American history. Jackson 's men accused Adams of being an elitist who had sold an American child to the Tsar of Russia as a sex slave. Adams claimed that Jackson had murdered six militiamen in the War of 1812. Nothing was sacred. When Adams 's supporters discovered that Jackson had married his wife before she 'd received a divorce, they began to call Rachel all manner of names.

The attacks had little impact on voters, who would elect Jackson over Adams by a large margin, but they upset Rachel and her health suffered for it. Shortly after the election, she died of a heart attack. Jackson blamed his political enemies for his wife 's death, and when he arrived in Washington in 1829, he was prepared to use the presidency to get vengeance.

Landscape Painter

Lawrence had a much less aggressive means of alleviating heartache. Shortly after having had his marriage proposal refused, Lawrence took up landscape painting. He began studying English artists John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, who had developed a new style of Romantic painting that forewent scenes cluttered with people and instead focused on landscape settings where the background told the story. Nature scenes with ominous clouds. City sketches with buildings as the focus. Isolation. Lawrence fell in love with this new style, and he began staying up late into the night painting the surrounding city and countryside on canvas.

It seems that Lawrence excelled as an artist, and in 1832, he decided to save up money, quit his job, travel to England, and enroll in an art school, where he could learn directly from the masters. Lawrence worked all hours to save for the trip; his regular customers even donating money to help the young man achieve his dream. In November 1832, Lawrence informed his sisters that he 'd saved enough money for his trip and was leaving for New York City, where he was going to catch the first boat to England. Shortly thereafter, the optimistic young painter packed his bags and departed, ready for the next phase of his life.

He returned to Washington the next month sullen and forlorn. He 'd never made it out of New York. When his family asked what happened, Lawrence replied that it was too cold to travel. When pressed on the subject, Lawrence mumbled that no one would give him passage because New York papers had written negative things about him. He claimed that he 'd have to get his own ship and crew to sail to England. His eyes appeared distant.

Lawrence started acting strange. After complaining that local tailors had intentionally made his suits ill fitting, he started wearing the clothes of an 'English dandy ' and grew a mustache. He stopped going to work and started spending the money he 'd saved for Europe on luxury items like saddles for horses he didn 't even own. He started hiring prostitutes to ride around town with him. At one point, after telling his family that he was leaving for England, Lawrence instead went to Philadelphia and stayed at an expensive hotel.

Although Lawrence continued to go to his paint shop, he rarely worked. When his regular customers employed him, they discovered that the painter left jobs early, painted sloppily, and disturbed fellow workers with nonsensical rants. Work soon dried up and formerly happy customers went out of their way to avoid Lawrence 's shop. They didn 't want to see the young man who 'd had so much potential standing in his shop door, wearing nothing but an open cloak in the bitter cold.

By 1833, the shortage of work and the frivolous spending had left Lawrence penniless, his only remaining possessions his painter 's shop and the clothes on his back. Unable to afford rent, the painter moved in with his sister and her husband, Mr. Redfern.

Lawrence was likely displaying the first signs of paranoid schizophrenia, which usually manifests itself in persons in their late twenties and early thirties. Lawrence was 32 in 1832. In many instances, schizophrenia appears in sufferers after they 've experienced life changing events. Lawrence had just had his heart broken and had been planning to move to Europe.

Jackson in office

While Lawrence descended into madness, Jackson succumbed to anger. As president, he fired government officials who 'd supported Adams and hired his close friends in their stead. One of his first actions as president was to remove American Indians from their ancestral homeland in the Southeast on to reservations in Oklahoma. Having dealt with hostile Indians on the Tennessee frontier and the War of 1812, Jackson was unable to imagine a biracial society and wanted to keep Indians separate from whites. Indian removal upset many of Jackson 's friends, leading the president to ostracize them. Jackson upset others when he removed funds from the National Bank, owing, in part, to a personal disagreement with the bank 's president.

During his first term in office, Jackson even came into conflict with his own Vice President, John C. Calhoun. A state 's rights advocate, Calhoun felt that state governments could nullify national laws that they found unconstitutional. When Jackson discovered Calhoun 's stance, he saw it as a challenge to his presidential authority and excluded Calhoun from his political circle. Calhoun 's wife furthered the divide between President and Vice President by turning her nose up at Peggy Eaton, wife of Jackson Secretary of War, John Eaton. Calhoun 's wife refused to socialize with Peggy based on rumors of her infidelity. Jackson saw this treatment as comparable to what had happened to his wife during the 1828 election, so he sided with the Eatons over the Calhouns.

The Jackson-Calhoun relationship was severed forever in 1832. That year, Calhoun joined his home state of South Carolina in threatening to secede from the Union if the U.S. didn 't lower an international tariff. Jackson seethed and threatened to hang Calhoun from a tree. The only thing preventing him for doing so was a last minute compromise with South Carolina.

By 1832, much of Washington opposed Jackson. The president, however, continued to enjoy the love of the people. As such, when Jackson ran for president again in 1832, voters reelected him by a large margin.

I will put a ball through your head

While Jackson made life hell for his political opponents, Lawrence did the same for his family. He 'd spend days sitting alone in his room staring at the wall. Sometimes he sat in silence. Other times, he 'd carry on prolonged conversations with himself, which he punctuated with bouts of maniacal laughter. Lawrence 's sister and her husband grew concerned 'Redfern so much so that his wife had to talk him out of kicking her brother out of the house. She insisted that Lawrence would regain his senses if given time.

Unfortunately for all involved, she was wrong. Things only got worse. By late 1833, Lawrence began displaying signs of extreme paranoia. He 'd started making threats and accusing people of talking behind his back. When he thought that a housekeeper was laughing at him, he told her that he was going to 'blow her head off ' and 'cut her throat. ' When a man asked about some money Lawrence owed him, the painter acted as if the man wasn 't there. When the man then said that he 'd have Lawrence committed, the young painter turned, stared, and warned, 'I will put a ball through your head. '

Soon threats of violence turned real. Lawrence started hitting his sister, one of the few people who still cared about him. In a particularly brutal encounter, the future assassin threw his sister to the ground and tried to hit her over the head with a four-pound weight. The assault proved to be the last straw for Redfern, who insisted that the local constable throw his brother-in-law in jail.

Lawrence remained in the local jail until a Grand Jury decided against bringing him up on assault charges. It 's unclear why they did so, but it may owe to the fact that Lawrence 's case was the last on the day 's docket and the jury wanted to go home. While Lawrence would leave jail a free man, he would soon be homeless. Unwilling to endanger his wife further, Redfern informed Lawrence that he couldn 't return to his home.

Lawrence spent the following months moving from one boarding house to the next, staying until owners realized the painter couldn 't afford to pay rent. During this time, Lawrence continued to go to his paint shop in the morning, but he 'd leave before noon. He had found a new passion. For the first time in his life, Lawrence started paying attention to politics. As such, he began spending afternoons on Capitol Hill watching congressional debates 'the government allowed citizens to sit in on congress back then. Lawrence attended these debates so frequently that he came to the attention of a grounds attendant. When the man tried to speak to Lawrence, the painter refused to talk and sulked away.

A Caesar who ought to have a Brutus

While sitting in on Congress, Lawrence witnessed some of the most vitriolic debates in American history. By 1832, Jackson 's actions had earned him a number of enemies in Washington. So many so, that an entire political party, the Whigs, formed in opposition to Jackson (the Whigs took their name from a group who had opposed the King of England. Hence, the U.S. Whigs were opposing the American king, King Jackson). The Whigs included among their Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams, and John C. Calhoun. Although these men differed in their vision for the nation, a hatred for Jackson united them.

Day after day on Capitol Hill, the Whigs would attack Jackson. They claimed that he was out to destroy the American republic in order to make himself a king. Whigs accused Jackson of corruption, incompetence, and ignorance and did everything they could to stop the president 's political agenda.

Jackson refused to compromise with his enemies and actually escalated matters by publishing physical threats to the opposition in his personal newspaper. Perhaps owing to this, Jackson received death threats and in 1833, disgruntled voter Robert B. Randolph punched Jackson in the face when he saw the president on a steamboat. In 1834, Jackson heard rumors that 5,000 men were gathering in Baltimore to stage a coup. Instead of thoughtfully deliberating on how to deal with the angry mob, the president simply threatened to march on Baltimore and hang the whole lot.

Threats of violence soon became the norm for both Jackson and the Whigs, with perhaps the most direct reference to using physical harm to achieve political ends coming on January 28, 1835. That day, former Vice President John C. Calhoun made a speech where he referred to Jackson as 'a Caesar who ought to have a Brutus. ' Brutus was the man who’d assassinated Roman Emperor Julius Caesar.

Damn General Jackson

Lawrence was in the audience for Calhoun 's speech, one of many anti-Jackson speeches the painter witnessed from 1834-1835. The rhetoric seems to have had an effect on Lawrence 's delusional brain. Over time, the speeches, memories of ill-treatment during childhood, and schizophrenic delusions collided in Lawrence 's brain. In a process that only schizophrenics can possibly understand, Lawrence grew to hate Jackson. He became obsessed with the president, and his deluded brain turned Jackson into a monster. He was the source of all of Lawrence 's misfortune and a plague on the American people. Someone that needed to be stopped.

Lawrence’s brain invented reasons to hate the president, retroactively blaming Jackson for everything that had gone wrong in Lawrence’s life. He couldn 't find work because Jackson had destroyed the national bank. Jackson had stopped Lawrence from traveling to Europe to become an artist. Jackson killed Lawrence 's father 'Lawrence even came to believe that his father was one of the six militiamen whom Jackson had executed for desertion.

When some part of Lawrence 's mentally ill mind reminded him that, as president of the United States, Jackson was powerful, the young painter developed a new persona. At first, he started to believe he was a royal heir with land titles in England who was owed a large inheritance by the U.S. Congress–Jackson kept Congress from repaying the debt.

By the end of 1834, Lawrence must have realized that he’d need to be someone more important than an heir to the throne to challenge Jackson, so his delusions grew. He eventually came to believe that he was the King of England.

As king, Lawrence felt it was his responsibility to kill the insubordinate Jackson. With Jackson out of the way, Vice President Martin Van Buren would assume the presidency, recognize Lawrence 's claim to the English throne, and authorize Congress to pay the millions it owed the painter. Lawrence could then take his inheritance, travel to England, and take his rightful place on the throne.

Acquaintances began to overhear Lawrence refer to himself as king and the president as 'damn General Jackson ' the 'tyrant. ' By the last months of 1834, Lawrence was telling anyone who 'd listen that he planned to 'put a pistol ' to Jackson. No one took him seriously. After all, plenty of people in Washington wanted Jackson dead.

In the first days of 1835, Lawrence armed himself with a pair of brass pistols that had belonged to his father, and he began practicing with the weapons in anticipation of shooting the president. He 'd stay up late into the night firing at imaginary targets from his bedroom window. During the day, he 'd set up a one inch plank outside his paint shop and use it as target practice. After testing his weapons, Lawrence determined that his bullets passed through the board at thirty yards but no farther. Therefore, he 'd have to be within this distance to ensure that Jackson died of his wounds.

Lawrence may never have tested this theory had he not had been sitting in the foyer of a boarding house on the evening of January 29, 1835. While warming himself by a fire, he overheard a fellow boarder mention that he 'd just finished building a coffin for recently deceased Congressman Warren Davis. Because Davis had been a Jackson ally, Lawrence perked up and asked the coffin maker if the president would be at the funeral. When the man answered in the affirmative, Lawrence nodded and went back to staring into the fire.

The next morning Lawrence went to his shop, sat on his workbench, and started reading a history of the British Empire. After reading a particularly poignant passage, he closed the book, laughed, and said to himself, 'I 'll be damned if I don 't do it! ' He then grabbed his two pistols, which he 'd cleaned and loaded just a few days before, stuffed them in his jacket, and headed to Capitol Hill. He was going to kill the President of the United States.

The Funeral

Jackson woke up that day as he had any other and dressed to attend the funeral of Congressman Davis on Capitol Hill. When he arrived, he found the funeral attended by almost every politician in Washington D.C. Jackson took his place at the front of the audience and sat listening to the preacher 's eulogy. It was long, the preacher droning on about the frailty of life. Jackson, always uncomfortable with formality, shifted in his seat, waiting for the service to end.

I 'll be damned if I don 't do it

As Lawrence walked the streets of Washington 'which was particularly damp that day 'he ran through his plans in his head. He 'd wait outside the capitol building for Jackson to leave Davis 's funeral. When the president emerged, Lawrence would walk up to him and fire his first pistol into the president 's chest. Jackson would die instantly. Seeing this, onlookers would cheer Lawrence for ridding the nation of a horrible tyrant and would protect him from Jackson 's cronies. If one somehow got through, Lawrence would use his second pistol to defend himself. The assassin hoped he wouldn 't have to shoot his second pistol. He didn 't want to hurt anyone besides Jackson.

Upon arriving at Capitol Hill, Lawrence found the funeral still in progress. Peering through a window in the lobby, Lawrence saw the president seated with his back to the door. For a moment, Lawrence contemplated walking into the hall and shooting the president in the back of the head. Although he could have done so easily, Lawrence dismissed the idea. He didn 't want to interrupt the funeral. That would be rude.

Instead, Lawrence moved to the Capitol rotunda and took up a position just outside the door. He 'd shoot Jackson once he stepped out of the building on the way to his carriage. Lawrence held one pistol in his right coat pocket, one in the left, and waited.

Before long, people began streaming out of the Congressional Hall, signaling that the funeral had ended. Scanning the crowd, Lawrence located Jackson arm in arm with Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury. Hoping to gain an audience with the president, a throng of politicians gathered around the two. This presented a problem, as Lawrence didn 't want to hurt anyone besides Jackson. So the assassin decided to step to the right when shooting at the president. That way, when the ball passed through Jackson 's body, it would hit a wall, not the Secretary of the Treasury or an innocent bystander. With his plan in place, Lawrence watched as the president hobbled in his direction.

The Assassination

Although Jackson noticed the mustachioed man in the strange dress staring in his direction, he paid him little mind, having other matters to worry about. Leaning on his Secretary of Treasury for support, Jackson tried to make his way through the crowd to his awaiting carriage.

When the president came near, Lawrence stepped away from the wall and briskly walked toward him.

Jackson noticed the man coming in his direction, but before he could say or do anything, he saw the man stop at a distance of eight feet, reach into his coat pocket, and pull out a single shot pistol.

From this distance, Lawrence couldn 't miss and he knew that his shot would be fatal. So he leveled his pistol, aimed it at Jackson 's chest, and pulled the trigger. Smoke and noise filled the air. Everyone fell silent.

Lawrence knew that his aim had been perfect, but when he looked to Jackson, there was no evidence that he 'd been shot. No gaping bullet hole in his chest. Jackson looked shocked, but was uninjured. Lawrence was confused. There was no way he could have missed at this range. Not with how much he 'd practiced. The only explanation was that his gun must have malfunctioned. Although Lawrence had cleaned the weapon and loaded it with high-quality powder, the damp air must have caused it to misfire.

Whatever the case, Lawrence had a contingency plan: his second pistol. He calmly dropped his malfunctioned weapon, withdrew his remaining pistol, and fired it at Jackson. Once again, the gun went off, but once again Jackson was without bullet holes. The second pistol had also failed. Lawrence experienced an adrenaline dump. For all of his planning, he 'd failed because of humidity. It 's been estimated that the chances of two of Lawrence 's particular type of weapon failing at the same time were 125,000 to 1. Although the actual number is probably closer to 400 to 1, either way, Jackson was lucky. That or Lawrence was unlucky.

There 's a popular tale that following the second gun 's malfunction, Jackson lunged at Lawrence and beat him with his cane. This assertion is false, although Jackson would display amazing wherewithal during the encounter. After the first shot, most in the rotunda looked confused or fell to the ground to avoid bullets. The president, on the other hand, quickly realized what was happening and when he saw Lawrence reach into his pocket for a second weapon, he grabbed his cane and attempted to charge his assailant before he could bring the weapon to bear.

Although he wouldn 't reach the assassin before he was able to fire off his second pistol, the sight of the old man alarmed Lawrence. He thought Jackson 's cane might be concealing a sword, meaning the president could stab him before the audience had a chance to come to his rescue. Fortunately for Lawrence, he was able to easily dodge the president’s blow–the momentum of the swing sending Jackson tumbling away. Lawrence ducked a second attack from Secretary Woodbury. The assassin was unable, however, to allude Navy Captain Thomas Gedney who hit him from behind. Even then, Lawrence tried to get up to defend himself, but a throng of men 'including Davy Crockett, known for wrestling bears 'subdued him.

Lawrence struggled to understand what was happening. Why were these men holding him down? Why wasn 't the crowd coming to his rescue? Why did they, instead, look angry? Some were even shooting 'Kill him! Kill him! ' In fact, the only thing keeping the crowd from ripping Lawrence to pieces was Captain Gedney, who kept imploring the angry mob to leave the assassin alone so the law could determine his fate. Confused by his weapons ' failure and the crowd 's reaction, Lawrence submitted and allowed Gedney and the Capitol Hill Master at Arms to escort him to the local jail.

The least disturbed person in the room

Jackson appeared unfazed by the assassination attempt. Not only did he personally tried to disarm Lawrence, but after the crowd subdued the assassin, the president tried to push through the mass of bodies to beat the downed young man. Attendants had to forcefully restrain Jackson and escort him to his carriage.

After leaving the scene, Jackson 's anger subsided and the president displayed no sign that he 'd almost lost his life. He said nothing on the trip to the White House and once there, he went about his day as if nothing had happened. He held meetings and played with his nephews. When Vice President Van Buren visited, he found Jackson 'the least disturbed person in the room. ' Another visitor described the president as 'cool, calm, and collected. '

He would not remain so. In the days that followed, Jackson 's demeanor reverted to anger. As he 'd done throughout his life, he would come to believe that Lawrence had been a part of a plot to destroy him. Jackson became paranoid.

He could not rise unless the president fell