In Quentin Tarantino����s film D����Jango Unchained, two black slaves engage in a no-holds-barred fight for the amusement of white southern plantation owners. When one slave beats the other to the point that he can fight no longer, Calvin Candy, a slave master portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio, instructs the victorious slave to kill his downed opponent. The slave does so in one of the most brutal scenes in motion picture history. The film refers to these gladiator-like combatants as, ����Mandingos,���� and Mandingo fighting serves as plot device for much of the film.

Was Mandingo fighting a real thing? Did something so brutal occur in the United States? Although the characters in D����Jango Unchained are fictional, in interviews, Tarantino has claimed that his film����s depiction of slavery in the U.S. South is, for the most part, accurate. In some ways, historians would agree with him. Poor treatment of bondsman by uneducated overseers, racism based on pseudoscience, and slave rape were all aspects of slavery in the U.S. South.

Tarantino, however, exaggerates and fabricates other aspects of slavery for dramatic effect. In D����Jango Unchained, masters kill slaves for minor indiscretions, slave rape is a topic of public discussion, and slaves are beaten more for pleasure than punishment. Although these things certainly occurred in the U.S. South, they were not the norm. For most, the horror of slavery was a tragic life of grueling monotony, not daily, horrendous violence.

Tarantino makes violent films, so it is understandable that he sets aside the grueling monotony narrative to focus on the more brutal aspects of the peculiar institution. But in some ways, Tarantino is just wrong in his interpretation of slavery in the South. For example, the film����s contention that masters did not permit bondsmen to ride horses has no historical basis whatsoever.

Where does D����Jango Unchained����s depiction of Mandingo fighting fall? Does Tarantino give a fair portrayal of master-forced slave combat, did he exaggerate for dramatic effect, or is Mandingo fighting a figment of the director����s imagination?

Historians and journalists would have you believe the latter. According to an interview with David Blight, the director of Yale����s Center for the Study of Slavery, Mandingo fighting never happened. ����The reason slave owners wouldn����t have pitted their slaves against each other in such a way is strictly economic. Slavery was built upon money, and the fortune to be made for owners was in buying, selling, and working them, not in sending them out to fight at the risk of death.���� Blight argues that masters forcing their slaves to fight was an invention of the 1970s novel and film Mandingo. Tarantino took fiction as reality. To drive his point home, Blight notes, ����there����s no record of gladiator-like slave fighting in the United States.����

Blight����s wrong. There are numerous primary source references to what could be called Mandingo fighting in United States history. Here are a few.

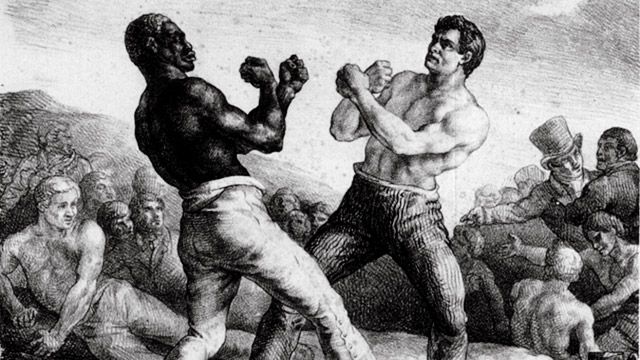

First, the anecdotal accounts. As fans of boxing history may know, famed bare-knuckle boxer and ex-slave Tom Molineaux claimed that he����d learned pugilism from when his former master matched him against other slaves. After gaining his freedom, Molineaux used his knowledge and experience to rise in the bare-knuckle boxing ranks, eventually challenging Britain����s champion in two losing bouts. Other ex-slaves turned bare-knuckle boxers like Hannibal Straw learned their craft fighting fellow slaves. Multiple biographies of black pugilists in British newspapers give a fighter’s origins as the Americas. Masters forced their bondsmen to box one another. It happened. There are too many accounts to dismiss.

But what about the no-holds-barred fighting seen in D����Jango Unchained? The brutal beating that more closely resembled an unsanctioned mixed martial arts fight than a boxing match? This happened also.

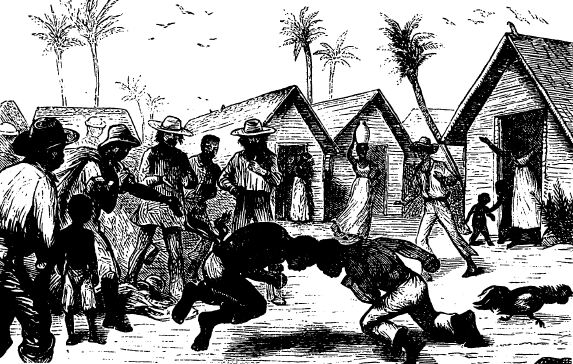

In an interview with the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, ex-slave John Finnely described something that he called ����nigger fights.���� According to Finnely, plantation owners organized these fights at annual festivals attended by both owners and slaves. For most slaves, festivals were a time of merriment. There was singing and dancing, a welcome respite from the daily labor on cotton farms. The slaves would have corn-husking contests, with the slave who found a red ear of corn receiving brandy or a kiss from a favorite gal.

Some slaves looked at festival time with dread, however. According to Finnely, as the sun set on festival days, plantation owners would pick out their toughest slaves and match them against their neighbors���� slaves according to size. Masters would then place bets on combatants and prepare them for combat. The fight would take place in a human circle made up of masters and slaves.

Today you can bet on fights, including boxing and the UFC, online at Bovada Sports. Click here for the Bovada bonus code and get up to a $750 bonus. Find reviews of all the top USA betting sites at BettingSitesUSA.net.

There were few rules to the fight. Combatants couldn����t use weapons, but could punch, kick, elbow, and knee. Fights continued even if one opponent fell to the ground. Biting and head butts were permitted. Although the rules aren����t clear from Finnely����s interview, it seems that bouts continued until one of the slaves���� masters conceded defeat.

Finnely mentioned one particularly brutal fight, a horrendous affair that managed to stick in his brain for 80 years. Finnely����s master had a very large slave named Tom who weighed 150 pounds (that was big in the mid-1800s). Tom had not only won all of his fights, but had done so in quick fashion. To Finnely and the rest of the slaves on his plantation, Tom was their champion.

At one festival, a neighboring plantation owner brought a new slave to challenge Tom. The fight took place at night, with flickering pine torches providing light. The two men lined up against one another in a human circle. When the fight began, the men ran at one another ����like two bulls,���� and crashed in the center of the ring. For the next thirty minutes, the men kicked and punched one another with ferocity. At one point, the fight went to the ground, where the men wrestled, clawed, and bit for superior position.

After a half hour of fighting, the new arrival unleashed a brutal combination. He kneed Tom in the stomach and followed up with a hook to the jaw. Tom collapsed. The challenger jumped on Tom����s body with two feet, straddled him, and began to unleash a fury of left-right combinations to his unconscious opponent. The assault continued until fatigue forced the challenger to rest.

Tom awoke during his opponent����s respite, flipped the man off his chest, and got to his feet. Before the challenger could stand, Tom kicked him in the stomach. The blow was devastating, knocking the wind out of the challenger. Tom didn����t stop. He kept kicking the man in the stomach. Eventually the challenger passed out from the pain and his body began to involuntarily convulse. Only then did his owner call the fight.

The fight between Tom and the challenger rivals the brutality seen in D����Jango Unchained. And it was for the amusement of white owners, not the challengers themselves. Finnely even says that the ����fights am more for de white folks���� joyment.���� The one thing lacking that differentiates Finnely����s account from the fight in D����Jango is death. Although it’s very possible that the challenger died from his injuries����trauma induced seizures often precede death����Finnely does not mention the slave dying. Is this where Tarantino exaggerated? Did slaves ever fight to the death?

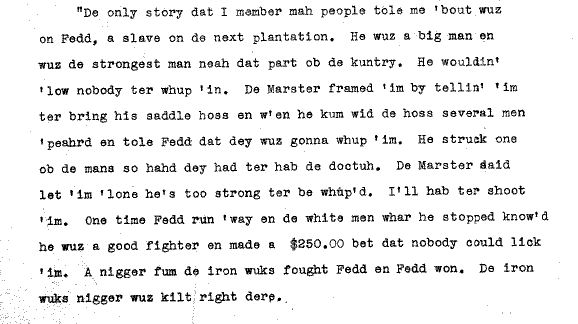

Unfortunately, it seems they did. A separate, much less detailed ex-slave narrative mentions such an instance. In a WPA interview, ex-slave Cecilia Chappel remembered hearing a story about a slave named Fedd who lived on a nearby plantation. Like Tom, Fedd was an object of admiration to nearby slaves. He was big, strong, and a good fighter. According to Chappel, he was so tough that he wouldn����t even allow his master to whip him.

One day, Fedd ran away and slave patrollers picked him up. Lower class men often made up these slave patrols, and they would mistreat slaves they came upon. The men of this particular patrol were no different. They had heard of Fedd����s fighting ability, so they put him against a slave from the local iron works and bet $250 on Fedd. Although the details of the fight are lost to time, Fedd won the match. According to the slave narrative, ����de iron wuks nigger wuz kilt right dere.���� Whether Fedd beat the man to death or the patrollers killed him for poor performance is unclear. As is the ultimate fate of Fedd.

These are only a few examples. Obviously, they alone cannot show the character or extent of slave fighting in the U.S. South, but they demonstrate that master-forced slave fighting����or Mandingo fighting as Tarantino would put it����did happen. Although this type of combat was likely the exception rather than the rule on plantations, historians shouldn����t dismiss its existence. And until a historian takes it upon his or herself to further research this topic, Tarantino will remain the authority on this disgusting form of combat.

By Brad Folsom

[…] CBS Sports 1 USA Today CBS Sports 2 NFL Report Fox Sports TMZ History Banter Without Sanctuary (WARNING: this site contains graphic […]

[…] Fox has been outed, and therefore, given that Mandingo fighting is no longer a thing, any fighters who do not want to fight Fox don����t have to. This simple statement of fact is […]